The world's superpowers convened in 1945 at the Black Sea port of Yalta to redraw the map of Europe following the defeat of Nazi Germany. This pivotal meeting resulted in the division of Europe, effectively delivering Eastern Europe to Soviet control and significantly dismembering Poland. Notably, the countries impacted by these decisions were neither represented nor consulted during the negotiations. As President Trump prepares for a meeting with President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia in Alaska, there is increasing anxiety among Ukrainians and Europeans regarding the possibility of a second Yalta, a term that now evokes deep fears of territorial concessions.

With the potential for negotiations between Trump and Putin to involve "land swaps" over Ukrainian territory, sentiments in Eastern Europe are fraught with tension. Peter Schneider, a prominent German novelist and author of “The Wall Jumper,” expressed that “Yalta is a symbol of everything we fear.” He emphasized that the original Yalta conference divided the world into spheres of influence, handing over countries to Stalin. Schneider warns that Putin’s ambitions appear to echo those historical decisions, with Ukraine being just the starting point of a broader agenda.

Yalta, located in the Russian-annexed region of Crimea, has become a powerful symbol of how superpowers can determine the fates of nations without their input. Ivan Vejvoda, a political scientist from the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna, highlighted that this moment marked a significant division in Europe, locking Eastern Europeans into a fate decided by external powers. He noted that today’s geopolitical landscape is different, yet the essence remains the same: critical decisions are still made on behalf of nations that have no voice in the matter. This reality is a source of national trauma for many in Eastern Europe, including Estonia, as articulated by Kadri Liik, an expert on Russia at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

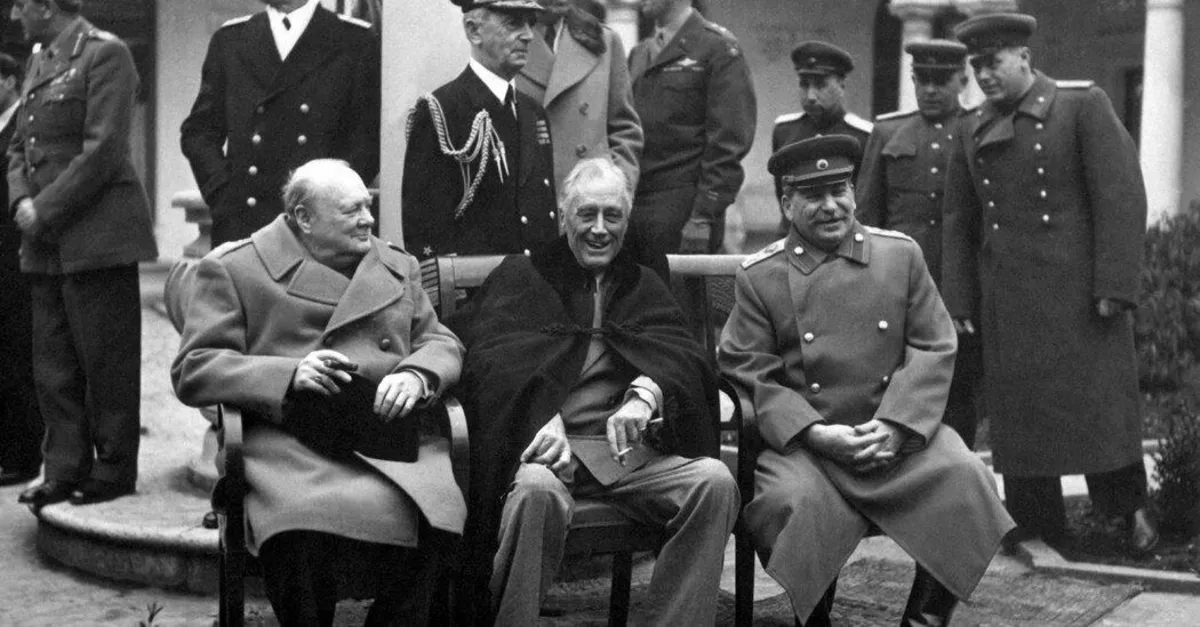

The original Yalta summit occurred in February 1945 when the defeat of Germany was already imminent, following the liberation of France and Belgium. The subsequent Potsdam Conference in July reaffirmed the division of Europe into Western and Soviet spheres. At the time, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill were both in declining health, and many Eastern Europeans felt that the leaders were overly trusting of Stalin's promises regarding free elections in occupied territories. As Serhii Plokhii, a Ukrainian history professor at Harvard, pointed out, Yalta has become synonymous with betrayal, particularly in Poland, where the conference's discussions on borders were especially contentious.

While there are notable differences between the Yalta Conference and today’s geopolitical discussions, Plokhii emphasizes that Stalin, despite being a troublesome ally, was pivotal in the defeat of the Nazis. Roosevelt and Churchill were focused on improving conditions for territories already under Soviet control rather than negotiating about regions held by Allied forces. The reluctance of Washington and London to expand the war further complicated the dynamics of the Yalta discussions.

Historian Timothy D. Snyder argues that the upcoming Alaska summit is “morally less defensible” than the Yalta meeting, primarily because Putin does not share the same status as an ally that Stalin once had. Snyder emphasizes that Russia, under Putin, is currently engaged in an unprovoked war, unlike the Soviet Union, which was fighting against Nazi Germany. This situation raises significant concerns about the legitimacy of negotiating territorial concessions when the aggressor is not a historical ally but an active perpetrator of conflict.

Today, Putin’s demands for Ukrainian territory echo historical moments such as the 1938 Munich Agreement, where Neville Chamberlain negotiated with Adolf Hitler over Czechoslovakia, a nation that was not represented at the talks. Plokhii notes that while Churchill and Roosevelt faced criticism for their decisions at Yalta, it was Chamberlain who became infamous for his role in the Munich Agreement. Snyder draws parallels between the demands of Hitler for the Sudetenland and Putin’s current territorial aspirations, highlighting the potential consequences for Ukraine’s defense if forced to concede critical regions like Donbas.

In conclusion, as the specter of a second Yalta looms, the lessons of history remind us of the importance of inclusive dialogue and the potential ramifications of decisions made without the involvement of affected nations. The fears articulated by Eastern Europeans today resonate deeply within the historical context of Yalta, posing a critical question about the future of sovereignty and self-determination in the face of great power politics.