Scientists are making significant strides in understanding how human ovaries develop their lifetime supply of egg cells, known as ovarian reserve. A groundbreaking study, published on August 26 in the journal Nature Communications, has meticulously mapped the emergence and progression of the cells and molecules that contribute to the ovarian reserve in monkeys. This research covers the critical phases of ovarian development, starting from the early stages in an embryo to six months after birth.

This comprehensive map addresses significant gaps in our understanding of ovarian biology. Amander Clark, a developmental biologist at UCLA and co-author of the study, highlighted the importance of this work, stating that researchers can now utilize this mapping to create improved laboratory models of the ovary. These models are essential for studying reproductive diseases associated with the ovarian reserve, such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a complex hormonal disorder that can lead to infertility.

Ovaries are the primary female reproductive organs, serving two vital functions in female health: the production of egg cells and the secretion of sex hormones like estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone. Ovarian development begins in embryos approximately six weeks post-fertilization. In the early stages, germ cells—precursors to egg cells—divide and connect to one another, forming intricate chains known as nests. When these nests break apart, individual egg cells are released and encased by specialized cells called pregranulosa cells.

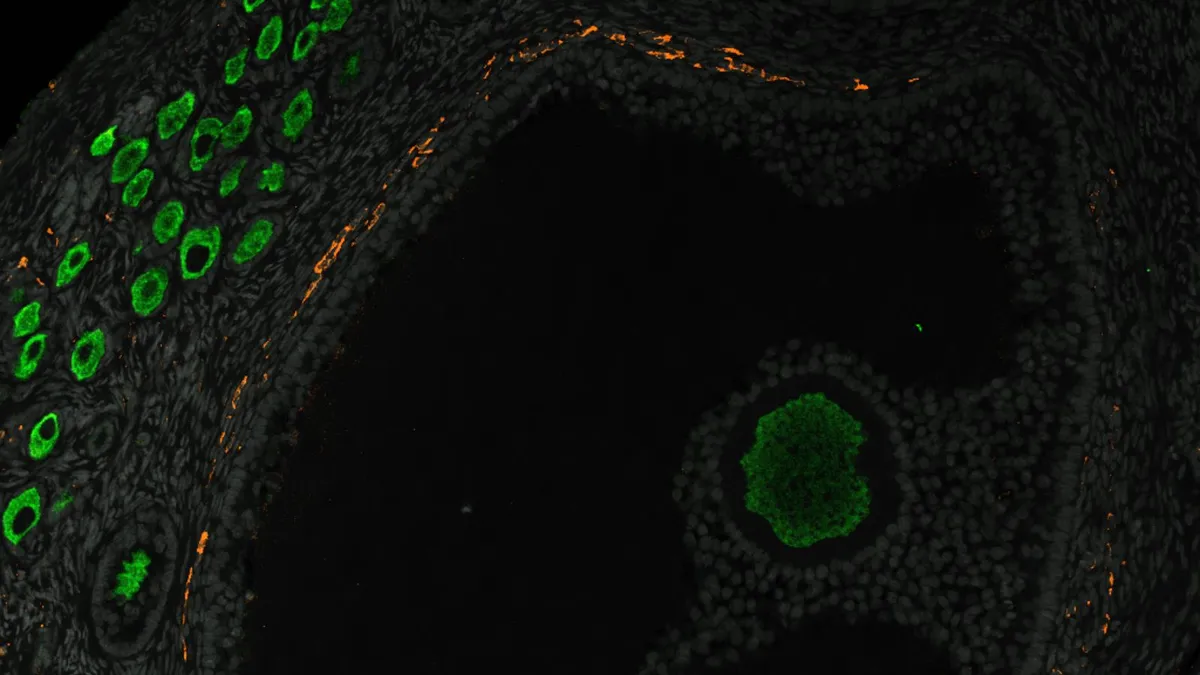

Pregranulosa cells play a crucial role in supporting young eggs and signaling when maturation should occur. These encased eggs, identified as primordial follicles, constitute the ovarian reserve. Formation of primordial follicles commences around 20 weeks after fertilization, clustering along the inner edges of the ovaries. As the follicles nearest to the ovary's center mature, they grow and produce essential sex hormones, ensuring the ovaries fulfill their roles in egg production and hormone release.

Many ovarian diseases stem from issues within the ovarian reserve's cellular structure. Although the precise cause of PCOS remains elusive, it is linked to dysfunction in primordial follicles. Despite the implications of these conditions, research into their development has been limited. Understanding how and when the ovarian reserve forms during pregnancy could illuminate why certain diseases and fertility issues emerge later in life, which is the primary objective of this study, according to Clark.

To investigate the origins of ovarian reserves in primates, Clark and her team studied a monkey species that shares physiological similarities with humans. This makes it an effective model for understanding human ovarian development. The research involved harvesting female monkey embryos and fetuses at various developmental stages, focusing on key time points: day 34 (the differentiation of sex organs), day 41 (early ovarian growth), days 50-52 (end of the embryonic period), day 100 (expansion of the egg nest), and day 130 (formation of primordial follicles).

The researchers analyzed the positioning and molecular characteristics of ovarian cells to identify critical events in the formation of the ovarian reserve. They discovered that pregranulosa cells emerge in two distinct waves, with the second wave occurring between days 41 and 52, marking the formation of pregranulosa cells that will eventually surround young eggs to create primordial follicles. Additionally, the study identified two genes that appear to be active before this second wave, suggesting that further exploration of these genes could reveal insights into the developmental origins of ovarian reserve issues.

Interestingly, the team found that prior to birth, the ovary undergoes practice rounds of folliculogenesis. This means that shortly after the ovarian reserve is established, some centrally located follicles mature and begin producing hormones. Understanding why these follicles typically activate could provide valuable insights into the causes of PCOS.

Despite these advancements, experts caution that the study examines a highly dynamic period of development, during which cellular composition can change significantly. Luz Garcia-Alonso, a computational biologist at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, noted that the researchers have substantial time gaps between their observations. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of this intricate developmental stage, it is vital to collect more detailed data at additional time points.