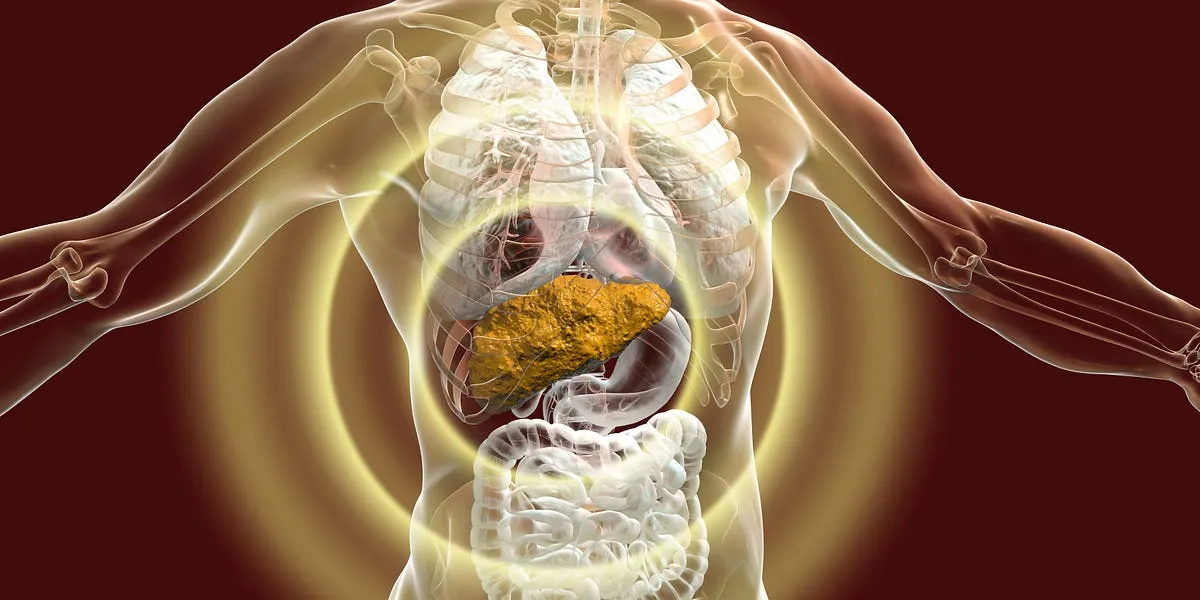

Hepatitis B is a highly transmissible, blood-borne disease that has been dubbed a “silent killer.” This designation stems from its ability to become chronic without showing symptoms for many years. Unfortunately, the absence of symptoms can lead to devastating consequences, such as cirrhosis or liver cancer, often emerging suddenly and unexpectedly. In the 1970s, Alaska faced one of the most severe threats from hepatitis B, particularly within its Native population, where the infection rate soared to alarming levels.

During this period, some tribes in Alaska reported infection rates as high as 15 percent, a stark contrast to the national average of just 1 percent. The impact was tragic, especially among children who contracted the virus at birth or during infancy, typically through maternal transmission or close contact with infected adults. Heartbreaking stories emerged, including that of patients who succumbed to liver cancer before even reaching adulthood.

Dr. Brian McMahon, a physician who treated many of these cases, recounted a particularly poignant story of an 18-year-old patient. She had a perfect 4.0 GPA and a scholarship to the University of Alaska, dreaming of becoming a teacher. However, persistent stomach pains led her to seek medical attention just two weeks before graduation. Tragically, she was diagnosed with liver cancer caused by hepatitis B and passed away shortly after. Dr. McMahon’s experience illustrates the harsh reality of this disease, which often goes undetected until it is too late.

In the early 1980s, hope emerged in the form of a highly effective hepatitis B vaccine. State officials collaborated with tribal leaders to implement a vaccination program that prioritized newborns, children, and caregivers. This initiative quickly expanded to include the entire tribal population, showcasing an impressive logistical effort, with health workers delivering doses to some of Alaska's most remote regions via single-engine planes.

The outcomes of this vaccination campaign were nothing short of remarkable. Alaska’s hepatitis B rates plummeted, and cases among children within the tribes effectively disappeared. Dr. McMahon stated, “We haven’t had hepatitis B-related cancer in kids for thirty years.” The eradication of the disease in children is a testament to the power of vaccination.

The success of the hepatitis B vaccination in Alaska captured the attention of federal officials, particularly the scientists on the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Recognizing the need for a national strategy, ACIP recommended in 1991 that hepatitis B shots be administered universally, starting right after birth. This policy shift has led to a staggering reduction in acute hepatitis B cases among children, with a decrease of over 99 percent nationwide, while rates among adults have also declined significantly.

The campaign against hepatitis B vaccination stands as one of the most significant public health accomplishments in recent decades, as noted on the CDC's own website. However, this achievement is now facing serious threats from movements against vaccination, notably the efforts led by Robert F. Kennedy Jr. The repercussions of this resistance could begin to unfold in the near future, jeopardizing the progress made against this silent killer.