On August 27, 2025, the Gemini South 8.2-meter telescope, equipped with the Gemini Multi-Object Spectrograph (GMOS), conducted deep imaging of the interstellar object 3I/ATLAS. This groundbreaking observation unveiled a subtle teardrop-shaped tail in the anti-Sun direction, a significant finding in the study of interstellar comets. At the time of the observation, 3I/ATLAS was located at a distance of 2.59 times the Earth-Sun separation.

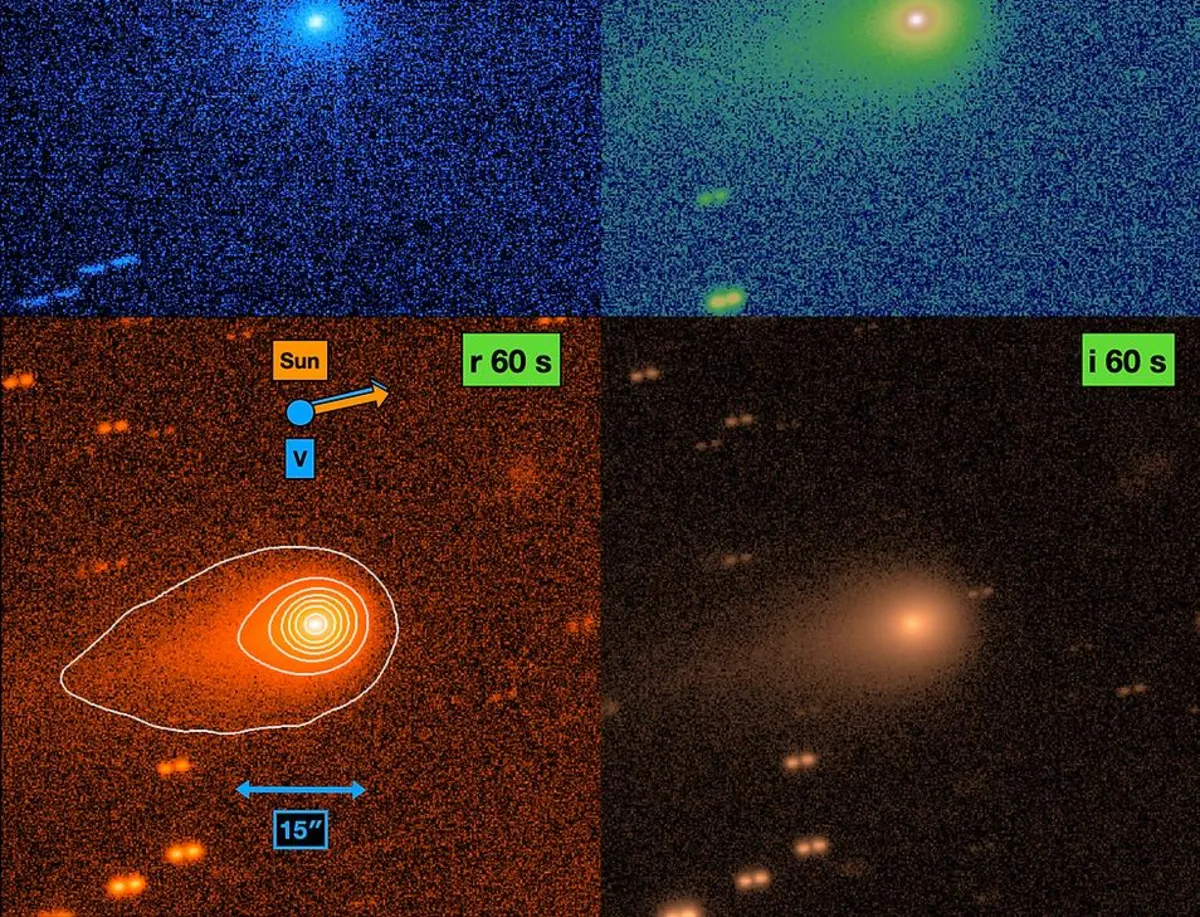

The Gemini South Observatory, perched on the Cerro Pachón mountain in the Chilean Andes, is renowned for its powerful imaging capabilities. The images captured during this observation were taken across various spectral bands: u (upper left), g (upper right), r (lower left), and i (lower right). These bands correspond to wavelengths of 0.365, 0.467, 0.616, and 0.747 micrometers respectively, showcasing the extensive tail behind 3I/ATLAS, which measures approximately 30 arcseconds or about 56,000 kilometers long, oriented towards the southeast.

The observations also noted that the coma surrounding 3I/ATLAS is around 10 arcseconds or 18,800 kilometers wide, presenting a much more extended appearance compared to its compact look in earlier images from July 2025. Data gathered on August 6, 2025 by the Webb Telescope confirmed the presence of a carbon dioxide (CO2) gas plume enveloping 3I/ATLAS, with significantly lower concentrations of water (H2O) and carbon monoxide (CO). This finding aligns with earlier reports from the SPHEREx space observatory, which mapped the CO2 plume extending out to 348,000 kilometers around the comet.

Analysis of the gas emissions from 3I/ATLAS reveals inferred mass loss rates of 130 kilograms per second for CO2, 6.6 kilograms per second for H2O, and 14 kilograms per second for CO. Notably, the H2O mass loss rate is only 5% of the CO2 output, which contrasts with typical expectations from a water-rich comet. The shape of the gas plume has been influenced by the solar wind and solar radiation pressure, forming a distinctive teardrop configuration.

Before my morning jog at sunrise, I calculated that the outer edge of the CO2 plume observed by SPHEREx is defined by the point where the ram-pressure of the solar wind matches that of the CO2 outflow. Remarkably, early data from NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) indicated that 3I/ATLAS may have exhibited activity and a surrounding glow of scattered sunlight at a much larger heliocentric distance of 6 times the Earth-Sun separation. At this distance, sunlight does not provide sufficient warmth to initiate cometary activity.

The flux detected by the SPHEREx observatory at a wavelength of 1 micrometer suggests that 3I/ATLAS might possess a massive nucleus or a dense scattering cloud with a diameter of 46 kilometers. If composed of solid material, this size implies that the mass of 3I/ATLAS is a staggering one million times larger than that of the previous interstellar comet, 2I/Borisov. This significant mass discrepancy raises questions, as numerous smaller objects like 2I/Borisov should have been detected prior to finding such a colossal interstellar object.

Adding to the intrigue, recent spectroscopic data from the Very Large Telescope in Chile detected unexpected elements, including cyanide and nickel without iron, in the gas plume surrounding 3I/ATLAS. This unusual finding suggests possible industrial production of nickel alloys, as natural comets typically display both iron and nickel, produced simultaneously in supernova explosions.

As 3I/ATLAS approaches its perihelion on October 29, 2025, its surface temperature will rise, leading to increased outgassing and interactions with stronger radiation and solar wind pressures. This high-stress environment may finally unveil the true nature and origin of 3I/ATLAS, answering the fundamental questions that continue to perplex astronomers.