Using cutting-edge DNA analysis, scientists have made a groundbreaking discovery regarding an ancient human relative known as the Dragon Man. This intriguing mystery began with the discovery of a giant human-like skull by a Chinese laborer in Harbin City, China, in 1933. The skull remained buried until 2018 when the laborer's family unearthed it from a well and subsequently donated it to the scientific community for further study.

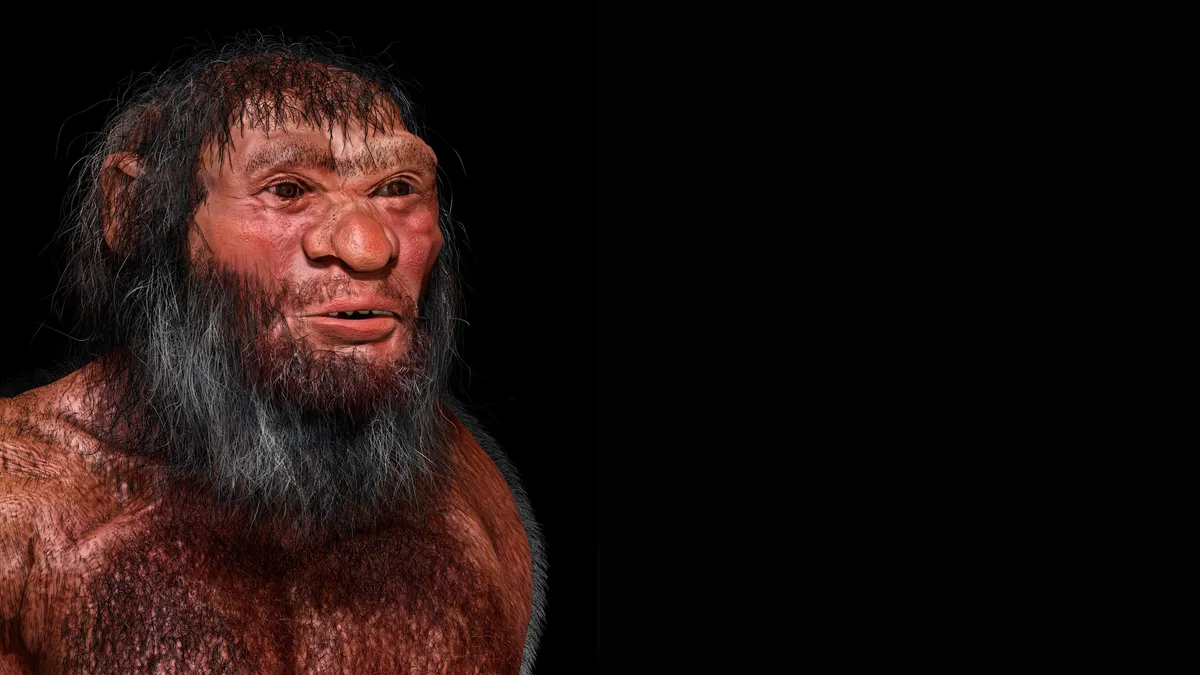

The enormous cranium, characterized by a long, low braincase, a pronounced brow ridge, a broad nose, and large eyes, led experts to propose a new species name — Homo longi, or Dragon Man — in 2021. Over the past few years, however, there has been significant debate among researchers regarding whether Dragon Man represents a distinct species or is instead a member of the ancient human group known as the Denisovans.

On June 18, two pivotal studies published in the journals Science and Cell have resolved this ongoing debate, confirming that Dragon Man is indeed linked to the Denisovans. Initially, scientists faced challenges in extracting an ancient genome from the skull's bones and teeth, but they successfully retrieved DNA from hardened plaque on the teeth and information regarding proteins from an inner ear bone.

The mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) recovered from the skull indicated that Dragon Man was related to an early group of Denisovans that lived in Siberia between 217,000 and 106,000 years ago. This finding suggests that the Denisovans had a much broader geographical presence across Asia than previously understood, as noted in the Cell study.

In addition to analyzing DNA, researchers conducted a thorough investigation of the skull's proteome, which encompasses the proteins and amino acids present in the skeleton. By comparing this proteomic data with those of contemporary humans, Neanderthals, Denisovans, and nonhuman primates, a distinct connection was established between the Harbin cranium and early Denisovans, as highlighted in the Science study.

The findings provide the first comprehensive morphological blueprint for Denisovan populations, addressing a long-standing question about their physical appearance. In essence, the research suggests that Denisovans looked like Dragon Man.

While the identity of the massive skull has been largely clarified, experts continue to debate its classification as Homo longi. Chris Stringer, a paleoanthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London, emphasized that this work enhances the likelihood that the Harbin skull represents the most complete Denisovan fossil discovered to date, although he maintains that Homo longi remains a suitable designation for this small group.

Furthermore, the new identification of the Harbin skull as a Denisovan urges experts to reevaluate their understanding of human evolution in Asia, particularly during the Middle Pleistocene epoch (approximately 789,000 to 126,000 years ago). This era was notable for the coexistence of at least three distinct hominin species — humans, Neanderthals, and Denisovans — who often interbred, leading to the term “muddle in the middle” to describe this complex evolutionary period.

Historically, knowledge of the Denisovan group has been limited to their DNA and a few fossils, unlike the well-documented remains of Neanderthals found across Europe and Western Asia over the past 150 years. With the recent identification of the Harbin skull and a jawbone discovered off the coast of Taiwan as Denisovan, paleoanthropologists now have definitive specimens for comparison, enhancing the understanding of these ancient humans.

Continued studies on the size and shape of Middle Pleistocene fossil skulls will be essential for elucidating relationships among these ancient hominins, especially as DNA tends to degrade in older fossils. Stringer notes that there is still much to be learned from extracting ancient DNA and proteomes, promising exciting advancements in the field of paleoanthropology.