A recent study has unveiled a new listing of the 50 most concerning pieces of space debris in low-Earth orbit (LEO), revealing that the majority of these hazardous objects are relics from over 25 years ago. These relics primarily consist of dead rockets left to drift through space after their missions concluded. According to Darren McKnight, the lead author of the paper presented at the International Astronautical Congress in Sydney, the issue of space debris is largely dominated by objects launched before 2000, which continue to pose significant risks.

In fact, a staggering 76 percent of the objects listed in the top 50 were placed in orbit during the last century, with 88 percent of these being rocket bodies. This statistic underscores the persistent problem of space debris, particularly as the objects travel around Earth at speeds nearing 5 miles per second. They occupy a heavily trafficked section of LEO, located between 700 and 1,000 kilometers (435 to 621 miles) above Earth's surface.

An impact with even a relatively small object at these high speeds can generate countless pieces of debris, potentially initiating a catastrophic chain reaction known as Kessler Syndrome. This cascading effect could lead to further collisions, significantly increasing the amount of space junk in orbit.

McKnight, who serves as a senior technical fellow at the orbital intelligence company LeoLabs, highlighted the findings prior to the paper's release. The analysis examined various factors such as the proximity of objects to other space traffic, their altitude, and mass. Notably, larger debris at higher altitudes poses a greater long-term risk, as they have the potential to create even more debris that can remain in orbit for centuries.

In terms of national contributions to the space debris problem, Russia and the Soviet Union dominate the list with a total of 34 objects. China follows with 10, the United States with three, Europe with two, and Japan with one. Among the worst offenders are Russia's SL-16 and SL-8 rockets, which account for a combined 30 slots in the Top 50. The top ten debris objects are as follows:

A Russian SL-16 rocket launched in 2004 Europe's Envisat satellite launched in 2002 A Japanese H-II rocket launched in 1996 A Chinese CZ-2C rocket launched in 2013 A Soviet SL-8 rocket launched in 1985 A Soviet SL-16 rocket launched in 1988 Russia's Kosmos 2237 satellite launched in 1993 Russia's Kosmos 2334 satellite launched in 1996 A Soviet SL-16 rocket launched in 1988 A Chinese CZ-2D rocket launched in 2019This recent report updates findings from McKnight's 2020 paper and delves deeper into the implications of removing the most hazardous debris. The analysis suggests that if missions were to retrieve all 50 identified objects, the overall potential for generating new debris in low-Earth orbit could be reduced by an impressive 50 percent. Furthermore, the removal of just the Top 10 objects could cut the risk of future debris by 30 percent.

However, there is a troubling trend emerging. Since January 1, 2024, there have been 26 rocket bodies left abandoned in low-Earth orbit, each expected to remain there for over 25 years. This timeframe is critical, as it aligns with guidelines set forth by the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee, which consists of representatives from major spacefaring nations including the United States, China, Russia, Europe, India, and Japan.

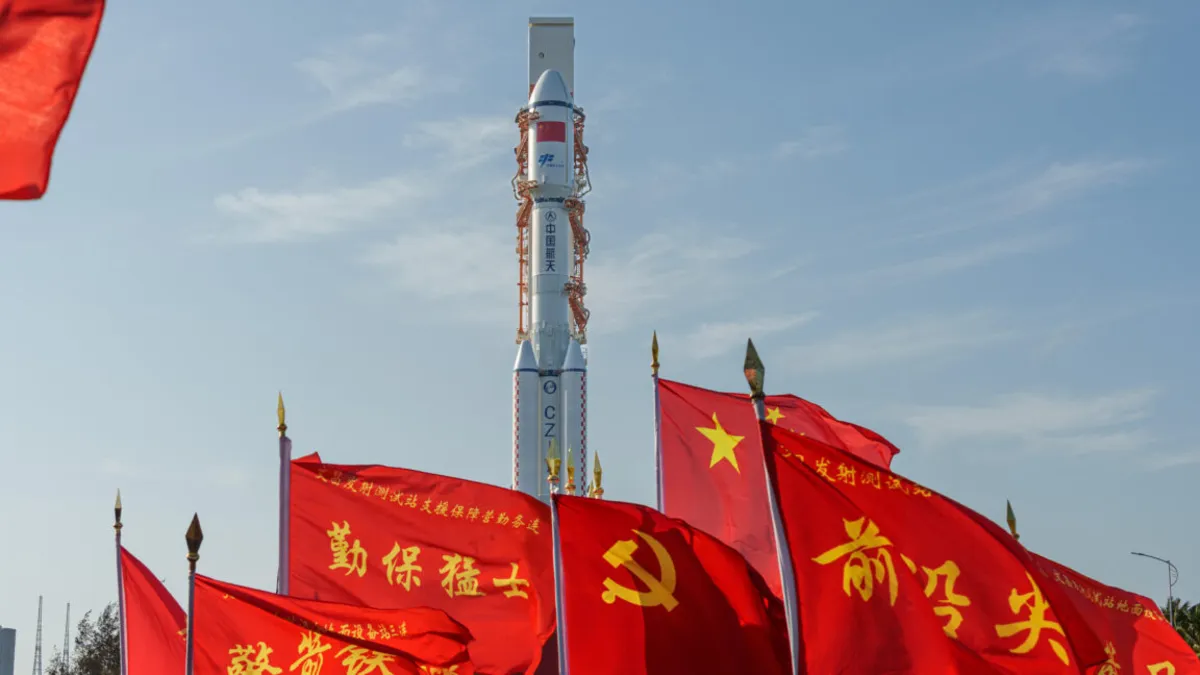

While the United States and European governments have implemented policies requiring launch companies to ensure that their spent upper stages are either deorbited or left in low enough orbits to reenter the atmosphere within 25 years, China has recently been criticized for frequently abandoning upper stages. In fact, over the past 21 months, China has launched 21 of the 26 new hazardous rocket bodies, each averaging over 4 metric tons (8,800 pounds).

China's ambitious plans for two megaconstellations—Guowang and Thousand Sails—are expected to exacerbate the space debris issue, as these projects will involve hundreds of rockets and thousands of communications satellites in low-Earth orbit. Although these satellites are designed to maneuver around space debris, the upper stages of the rockets used for their deployment have often been left in orbit, violating international guidelines.

Despite advancements in technology that could allow for the deorbiting of upper stages, many older models of Chinese rockets lack the capability to reignite their engines in space, leaving them stranded. Even when rockets are equipped with restartable engines, sufficient fuel must be reserved for deorbit burns, which reduces payload capacity. McKnight notes that while China has demonstrated the potential to deorbit rocket bodies, the average practice shows a tendency to leave debris behind.

In light of these challenges, McKnight and his coauthors have emphasized the importance of active debris removal initiatives. Although the concept is technically feasible, the question of funding remains unresolved. There is currently limited investment in debris removal initiatives by organizations like the European Space Agency and Japan's space agency. One promising project led by the Japanese company Astroscale recently completed a demonstration aimed at docking with a defunct rocket.

By taking proactive steps to remove even a small number of objects, McKnight believes it is possible to make a measurable impact on the potential for future debris generation and mitigate the risks associated with Kessler Syndrome. The urgency of addressing the growing problem of space debris cannot be overstated, especially given the recent addition of 26 new objects in the past two years.