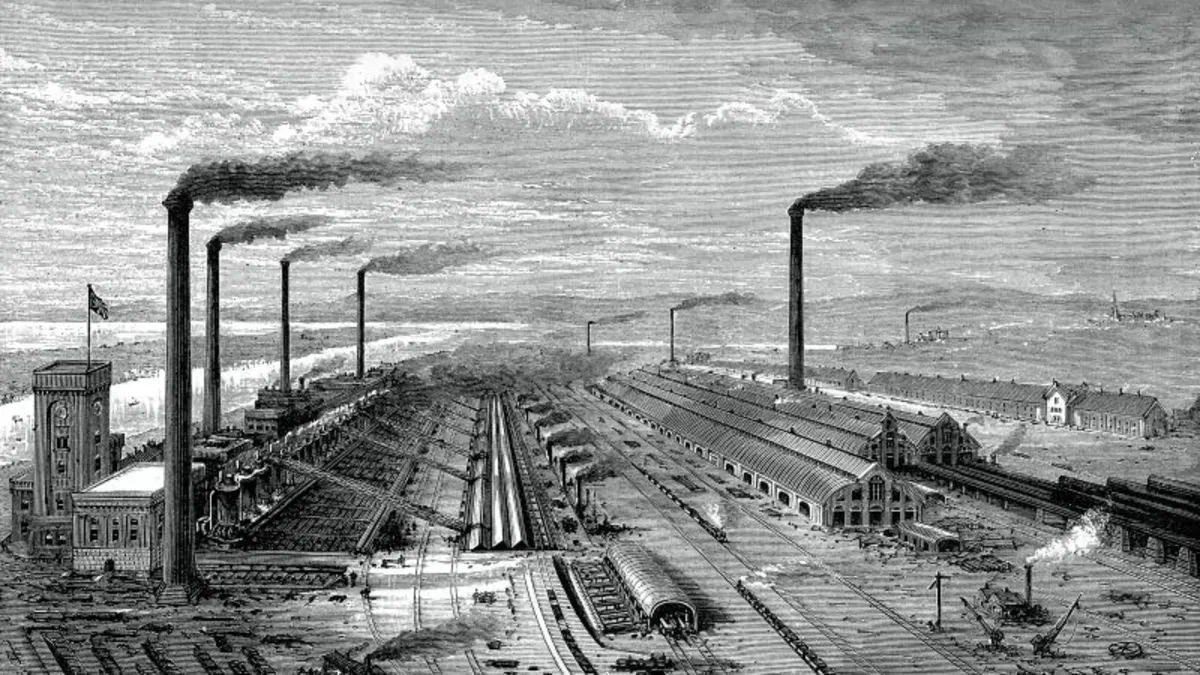

A groundbreaking study has unveiled that the human fingerprint on global warming was likely detectable in Earth's atmosphere much earlier than previously recognized. This research indicates that signs of human-caused climate change may have been evident as far back as 1885, preceding the invention of modern gas-powered cars and following the onset of the industrial revolution.

The findings were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, revealing that researchers utilized a combination of scientific theory, contemporary observations, and advanced computer models. Their work highlights the pressing need to track changes in the upper atmosphere, as humanity has potentially been influencing the planet's climate in a detectable manner for a longer period than previously thought.

Historically, scientists began recording surface temperature observations in the mid-19th century. The conventional belief was that a detectable human signal in surface temperatures emerged in the early-to-mid-20th century. However, this study challenges that notion by focusing on the stratosphere, the second layer of the atmosphere, where unique dynamics of climate change occur.

While greenhouse gas emissions primarily warm the troposphere, they have an opposite effect on the stratosphere, especially its upper regions. By examining climate models and using this knowledge, researchers sought to identify the earliest signs of human impact on climate. Lead author Ben Santer and co-author Susan Solomon expressed surprise at discovering such a clear human signal in the stratosphere well before the expected timeline.

The study revealed that a mere 10 parts per million increase in carbon dioxide concentrations between 1860 and 1899 was sufficient for scientists to detect a climate change signal in the 19th-century atmosphere. In stark contrast, carbon dioxide levels have surged by approximately 50 parts per million from 2000 to 2025, underscoring the rapid changes we are currently witnessing.

Gabi Hegerl, a climate scientist from the University of Edinburgh, emphasized that these results highlight the significant influence of greenhouse gas increases on the upper atmosphere compared to its natural variability. Andrea Steiner, a climate expert at the Wegener Center for Climate and Global Change, noted that this study confirms the effectiveness of atmospheric temperature change signals as early indicators of the success of climate mitigation efforts.

Both Santer and Solomon stressed the necessity of ongoing monitoring of the upper atmosphere. This message is particularly critical amid ongoing budget cuts to scientific research, with significant implications for climate satellite programs and monitoring initiatives at NOAA, NASA, and the Department of Energy. For instance, the proposed NOAA budget could eliminate essential carbon dioxide monitoring functions, while NASA's budget may cut vital climate-relevant satellite missions.

Santer poignantly remarked on the importance of public awareness regarding the risks associated with losing the capability to measure and monitor our changing world. Maintaining these capabilities is crucial for ensuring the safety and well-being of our planet as we navigate the challenges posed by climate change.