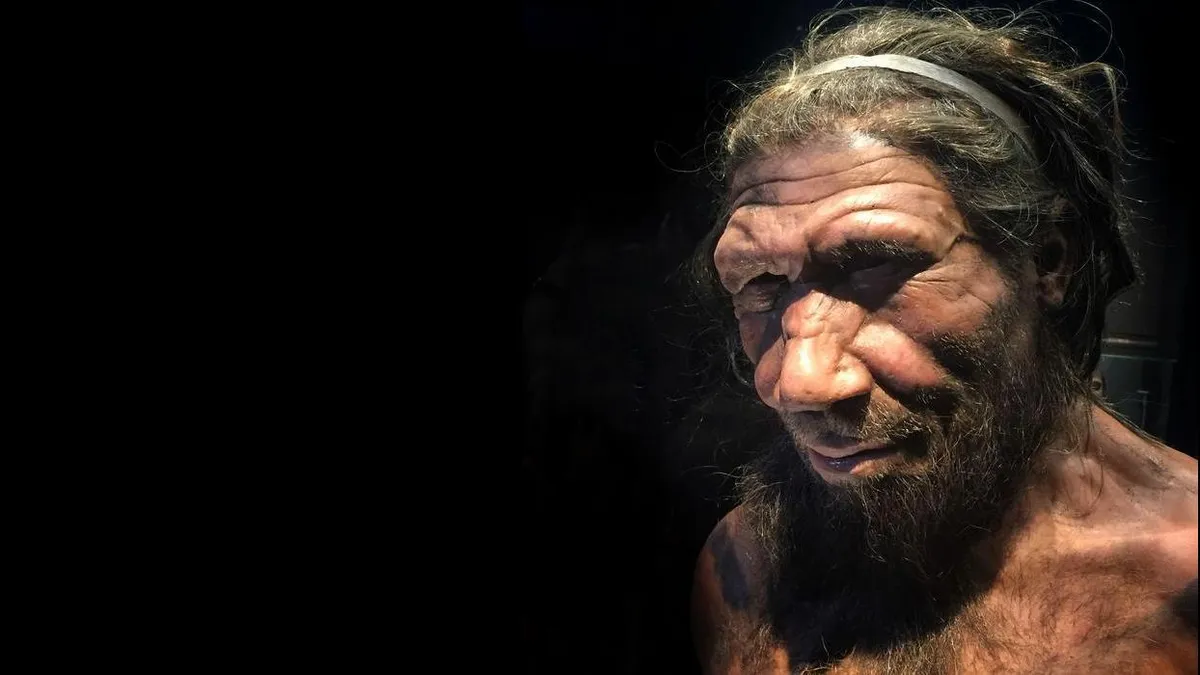

A groundbreaking study has revealed that a protein crucial for DNA synthesis, known as ADSL (adenylosuccinate lyase), exhibits significant differences between modern humans and our closest extinct relatives, the Neanderthals and Denisovans. Researchers propose that these variations may have influenced behavioral traits, providing insights into the evolutionary advantages that may have contributed to the survival of modern humans while our relatives disappeared. This research, conducted on genetically modified mice, opens new avenues for understanding the complexities of human evolution.

Modern humans diverged from Neanderthals and Denisovans approximately 600,000 years ago. The reasons behind the survival of Homo sapiens while these close relatives became extinct remain a mystery. To uncover potential genetic clues, the research team focused on the enzyme ADSL, which plays an essential role in synthesizing purine—the fundamental building block of DNA and various vital molecules. According to Svante Pääbo, a Nobel laureate and co-author of the study, ADSL is one of the few enzymes that underwent evolutionary changes in our ancestors.

The ADSL enzyme consists of a chain of 484 amino acids. Notably, the version present in almost all modern humans differs from that of Neanderthals and Denisovans by a single amino acid: the 429th amino acid is valine in modern humans, while it is alanine in our extinct relatives. This mutation likely emerged after the split from the lineage leading to Neanderthals and Denisovans, prompting researchers to investigate its potential impact on behavior.

Published on August 4 in the journal PNAS, the study found that the modern version of ADSL leads to elevated levels of substances that ADSL typically acts upon, particularly in the brain. This supports the hypothesis that the modern human variant is less active than the ADSL variant found in Neanderthals and Denisovans. In controlled experiments, female mice with the modern human version of ADSL demonstrated superior learning abilities, successfully connecting the presence of water with specific lights or sounds, compared to their counterparts lacking this variant.

Interestingly, the behavioral advantages associated with the modern ADSL variant were observed exclusively in female mice. The reason for this discrepancy remains unclear, as noted by study co-author Izumi Fukunaga. This complexity underscores the intricate nature of behavior and the potential influence of various genetic factors.

Further statistical analyses of Neanderthal, Denisovan, and modern human DNA from African, European, and East Asian populations revealed that mutations in the ADSL gene are more prevalent in modern humans than random genetic variations would predict. This suggests that these mutations provided some form of evolutionary advantage. However, previous studies have indicated that deficiencies in ADSL can lead to intellectual disabilities and other impairments, indicating a balancing act between the benefits and drawbacks of ADSL activity in modern humans.

While not all experts are convinced that these findings directly explain the survival of modern humans or the extinction of Neanderthals and Denisovans, the study’s methodology using mice to explore behavioral ramifications of genetic variations shows promise. Mark Collard, a paleoanthropologist who was not involved in the research, emphasized the potential for future studies to investigate the mechanisms through which changes in ADSL activity impact behavior, as well as how various genetic changes may interact.

As research continues, scientists aim to unravel the complexities of human evolution and the factors that have shaped our behavior over millennia. The investigation into ADSL offers a crucial piece of the puzzle in understanding the differences that set modern humans apart from our extinct relatives.