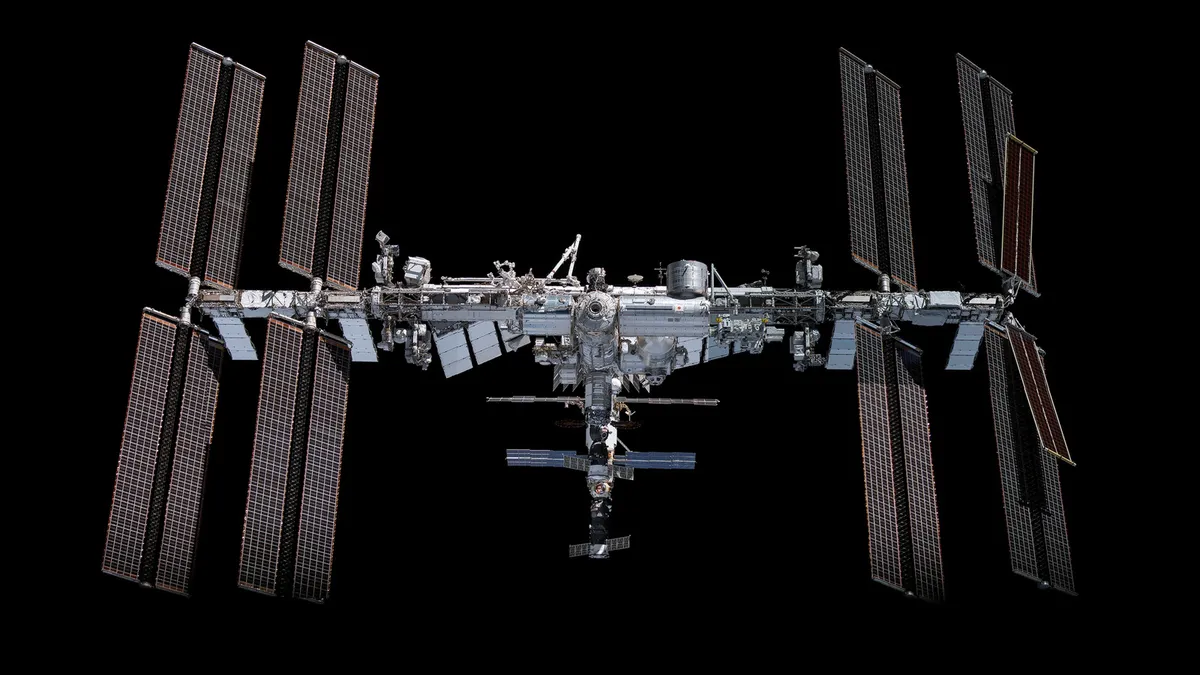

After more than two decades of groundbreaking research and international collaboration, NASA has announced its plans to decommission the International Space Station (ISS) by 2030. This iconic orbital laboratory has completed over 100,000 orbits around Earth, but due to aging infrastructure and rising maintenance costs, it can no longer remain in operation indefinitely. Instead of allowing the ISS to drift uncontrollably back into the atmosphere, NASA is preparing for a controlled descent to ensure a safe and precise final return to Earth.

Since its first module launched in 1998, the ISS has stood as a beacon of scientific progress and international collaboration. For many adults today, the ISS represents a significant part of their lives, as some weren't even born when the first astronauts boarded the station in November 2000. It has served as humanity’s permanent outpost in space, where astronauts from various countries conduct pioneering research across multiple fields, including medicine, physics, climate science, and spacecraft technology.

As NASA shifts its focus toward missions to the Moon, Mars, and beyond, it is time to bid farewell to this remarkable space station. To mitigate the risks associated with the ISS's decommissioning, NASA has devised a comprehensive multistep plan to guide the massive structure back into the Earth’s atmosphere safely. This carefully orchestrated strategy aims to prevent the potential hazards of debris from uncontrolled reentry.

The ISS will gradually lower its orbit due to natural atmospheric drag, a process that will be closely monitored and controlled by engineers on the ground. They will perform necessary reboosts and orbital adjustments to ensure the station maintains stability and orientation as it prepares for its final descent.

Once the last crew has returned to Earth, a specially designed spacecraft known as the U.S. Deorbit Vehicle (USDV) will approach the ISS. Developed by SpaceX under NASA’s guidance, this vehicle will act as a space tug, directing the ISS toward a remote area of the South Pacific Ocean known as Point Nemo, often referred to as the “spacecraft cemetery.” This region has historically served as a safe disposal site for satellites and space debris.

As the USDV executes its deorbit burn, the ISS will begin its descent into the denser layers of the Earth's atmosphere. During this phase, intense heating will cause most of the station to disintegrate and burn up, with any surviving fragments expected to harmlessly fall into the ocean. This controlled descent contrasts sharply with the uncontrolled reentries of smaller spacecraft, such as Skylab, which resulted in debris falling in populated areas like Australia. Given the ISS's weight of over 400 tons, an uncontrolled descent could pose unacceptable risks.

The decommissioning of the ISS will be the most complex reentry operation ever attempted. It requires meticulous coordination among international partners, including NASA, Russian Roscosmos, the European Space Agency, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, and the Canadian Space Agency. NASA's controlled deorbit plan not only prioritizes safety but also ensures a dignified conclusion for one of humanity's most ambitious symbols of science and cooperation.

Several overlapping factors contribute to the decision to decommission the ISS, the most significant being the station's aging infrastructure. Its modules, radiators, and other structural components have endured decades of harsh conditions in orbit, including cyclical heating and cooling, docking loads, and even a meteor impact that necessitated a rescue operation. As operational costs continue to rise, the question arises: how will NASA replace the ISS once it has deorbited?

A new era in low Earth orbit is already emerging. NASA's future role will shift from owning and operating the next orbital outpost to partnering with private companies engaged in developing new commercial space stations. Companies such as Axiom Space, Blue Origin's Orbital Reef, and Voyager Space's Starlab are leading the charge in creating innovative platforms that will serve as research hubs and manufacturing sites, as well as destinations for private astronauts. Instead of maintaining an aging government-operated laboratory, NASA plans to purchase time aboard these commercial stations.

The retirement of the ISS opens the door to innovation, potentially leading to lower costs and new opportunities in research, industry, and space tourism. Beyond low Earth orbit, NASA's ambitions extend toward the Moon and Mars. The Artemis program, for instance, aims to return humans to the Moon and establish a sustainable presence there, ultimately serving as a testing ground for technologies needed for the first crewed mission to Mars.

Nevertheless, the lessons learned from the ISS—such as life support systems, long-duration missions, and international collaboration—will be vital in achieving these ambitious deep-space goals. In this sense, the legacy of the ISS will not conclude with its descent into the Pacific; rather, it will continue to inspire every future spacecraft that ventures further into the cosmos.