A groundbreaking study has revealed that interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS is leaking water at an astonishing rate, akin to a fire hose running at full blast. Utilizing NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, scientists have successfully detected the chemical signature of water streaming from this remarkable celestial body. This discovery marks the first time researchers have observed such a phenomenon in an object originating from another star system, placing 3I/ATLAS among the rarest of cosmic visitors.

Water serves as the universal benchmark in comet science, providing a critical baseline for understanding how sunlight influences a comet's activity and the release of various gases. By identifying water in an interstellar visitor, astronomers can make direct comparisons with comets native to our own solar system. This offers a unique opportunity to gain insights into the chemical makeup of distant planetary systems.

“When we detect water — or even its faint ultraviolet echo, OH — from an interstellar comet, we're reading a note from another planetary system,” said study co-author Dennis Bodewits, a professor of physics at Auburn University. “It tells us that the ingredients for life's chemistry are not unique to our own.”

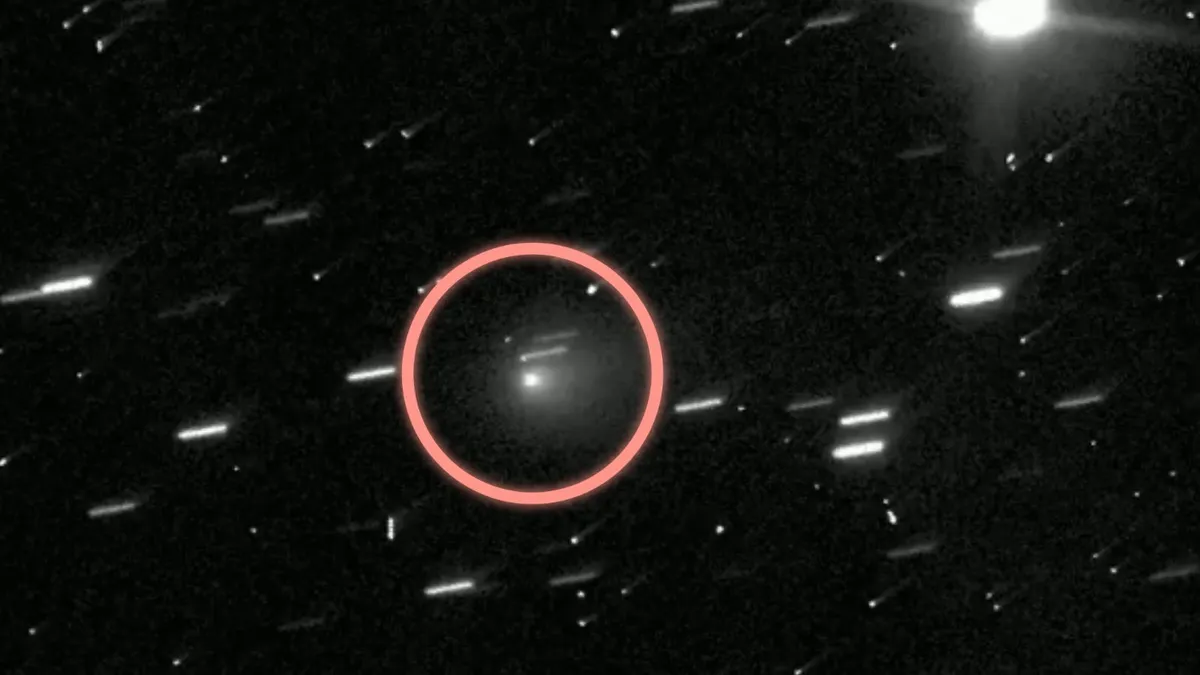

In July and August 2025, Bodewits and his research team utilized the Swift telescope to observe 3I/ATLAS when it was located approximately 2.9 times farther from the sun than Earth. This position is well beyond the region where water ice typically sublimates. Despite this distance, the Swift telescope detected the faint ultraviolet glow of hydroxyl (OH) — a byproduct of water molecules that have been dissociated by sunlight.

To capture this delicate signal, astronomers conducted a meticulous analysis, stacking dozens of short, three-minute exposures to accumulate over two hours of ultraviolet observations and an additional 40 minutes in visible light. The findings, published on September 30 in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, indicated that 3I/ATLAS is losing water at an impressive rate of approximately 40 kilograms per second. This outflow rate is comparable to the discharge of a fire hose running at full capacity.

The research team estimates that at least 8% of the comet’s surface must be active, a significantly higher percentage than the typical 3% to 5% observed in comets from our solar system. This unexpected level of activity may not stem from the comet's solid surface but instead from icy debris floating around it. Near-infrared observations from Gemini South and NASA's Infrared Telescope Facility suggest the presence of ice chunks within the coma — the cloud of gas and dust surrounding the nucleus. As these clumps are exposed to sunlight, they warm up and function like miniature steam vents in space, releasing water vapor despite the comet’s surface remaining too cold for direct sublimation.

Every interstellar comet discovered thus far has brought its own surprises. As Zexi Xing, a postdoctoral researcher at Auburn University and the lead author of the study, noted, “Oumuamua was dry, Borisov was rich in carbon monoxide, and now ATLAS is giving up water at a distance where we didn’t expect it. Each one is rewriting what we thought we knew about how planets and comets form around stars.”

Although 3I/ATLAS has since faded from the Swift telescope's view, it was recently observed by the European Space Agency’s Mars orbiters in early October, passing approximately 30 million kilometers from Mars. The agency plans to continue monitoring this interstellar visitor, with its Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) slated to observe the comet following its closest approach to the sun in November. This observation is expected to provide the most detailed view of 3I/ATLAS when it is anticipated to be at its peak activity. However, due to JUICE’s current position on the far side of the sun and its reliance on a slower backup antenna, scientists do not expect to receive data from these observations until February 2026.