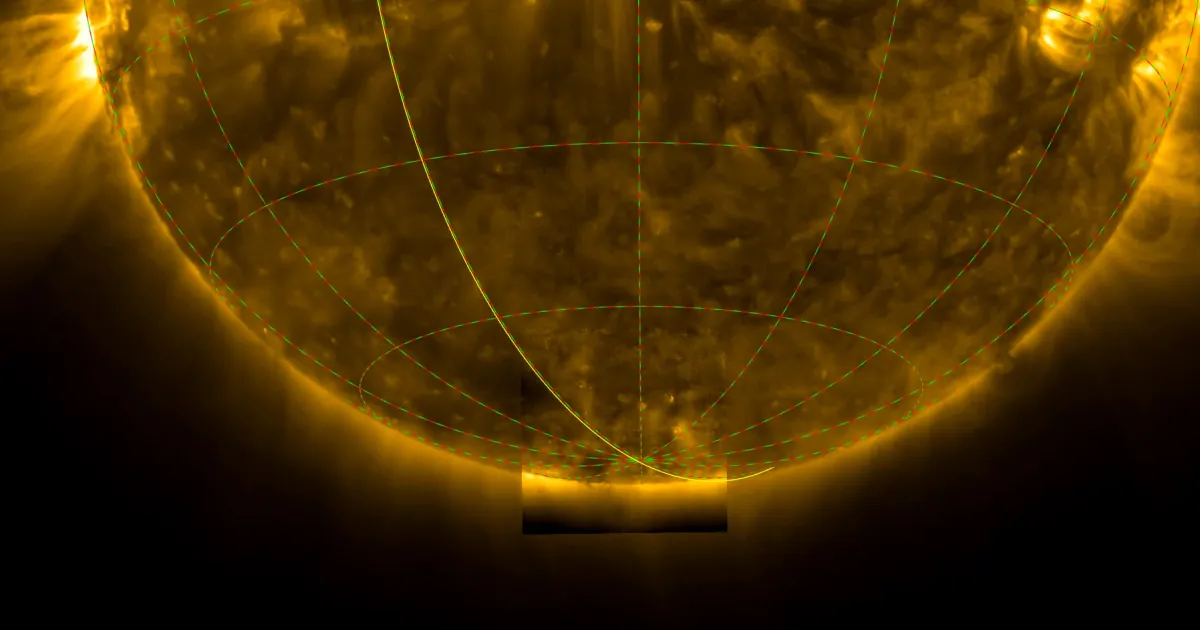

The first-ever images of the sun’s south pole reveal a chaotic array of magnetic activity in a previously unexplored region of our closest star. Captured by the Solar Orbiter spacecraft and released on Wednesday by the European Space Agency (ESA), these images provide fresh insights into the sun’s behavior, its magnetic field, and the mechanisms behind space weather.

“The sun is our nearest star, giver of life, and potential disruptor of modern space and ground power systems,” stated Carole Mundell, director of science at ESA. “It is imperative that we understand how it works and learn to predict its behavior. These unique views from our Solar Orbiter mission mark the beginning of a new era of solar science.”

The newly released images have already proven invaluable for heliophysicists, showcasing turbulent magnetic activity at the sun's south pole as it approaches the most active phase of its natural cycle. The solar cycle typically spans approximately 11 years, transitioning from a period of low magnetic activity to a highly active phase characterized by intense solar flares and solar storms.

During the peak activity phase, known as the solar maximum, the sun's magnetic poles undergo a flip, transforming the south pole into a magnetic north. However, the exact reasons for this phenomenon remain unclear, as do the precise forecasts for when it will occur. The Solar Orbiter spacecraft may help uncover some of these mysteries.

From its observations, scientists have identified magnetic fields exhibiting both north and south polarity at the sun’s south pole. This combination of magnetism is anticipated to last only a brief period during the solar maximum before the magnetic field undergoes a flip. Following this event, a single polarity is expected to gradually emerge at the poles as the sun transitions towards its quieter solar minimum phase, according to ESA.

“How exactly this build-up occurs is still not fully understood, so Solar Orbiter has reached high latitudes at just the right time to track the entire process from its unique and advantageous perspective,” explained Sami Solanki, director of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany and lead scientist for Solar Orbiter’s PHI instrument, which is responsible for mapping the sun’s surface magnetic field.

While scientists have previously captured close-up images of the sun, these have all been taken from around the sun’s equator by spacecraft and observatories orbiting along a plane similar to Earth’s path. The Solar Orbiter, however, has undergone close flybys of Venus, allowing it to tilt its orbit and view higher latitudes on the sun.

The recently released images were captured in late March when the Solar Orbiter was positioned 15 degrees below the sun’s equator, and shortly thereafter, 17 degrees below the equator—an angle sufficient to directly observe the sun’s south pole. “We didn’t know what exactly to expect from these first observations—the sun’s poles are literally terra incognita,” noted Solanki.

Launched in February 2020, the Solar Orbiter mission is a collaborative effort between ESA and NASA. In the coming years, the spacecraft’s trajectory is expected to tilt further, enabling even more observations of the sun's south pole. As such, the most detailed views may still be on the horizon, according to ESA.

“These data will transform our understanding of the sun’s magnetic field, the solar wind, and solar activity,” stated Daniel Müller, ESA’s Solar Orbiter project scientist.