The National Science Foundation's Daniel F. Inouye Solar Telescope has achieved a remarkable milestone in solar science by capturing images of the smallest magnetic loops ever observed in the sun's corona. This discovery could represent the foundational elements that drive the intense solar flares that frequently erupt from our star. Cole Tamburri, a researcher from the University of Colorado, Boulder, expressed the significance of this achievement, stating, "We're finally seeing the sun at the scales it works on."

Solar flares occur when magnetic field lines within the sun's outer atmosphere, known as the corona, become taut and subsequently snap, releasing vast amounts of energy. While this phenomenon has been understood for some time, the intricate details of magnetic reconnection and its relationship with solar flares remain subjects of ongoing research. A crucial question in this field is: how small can these coronal loops be, and what role do they play in powering solar flares?

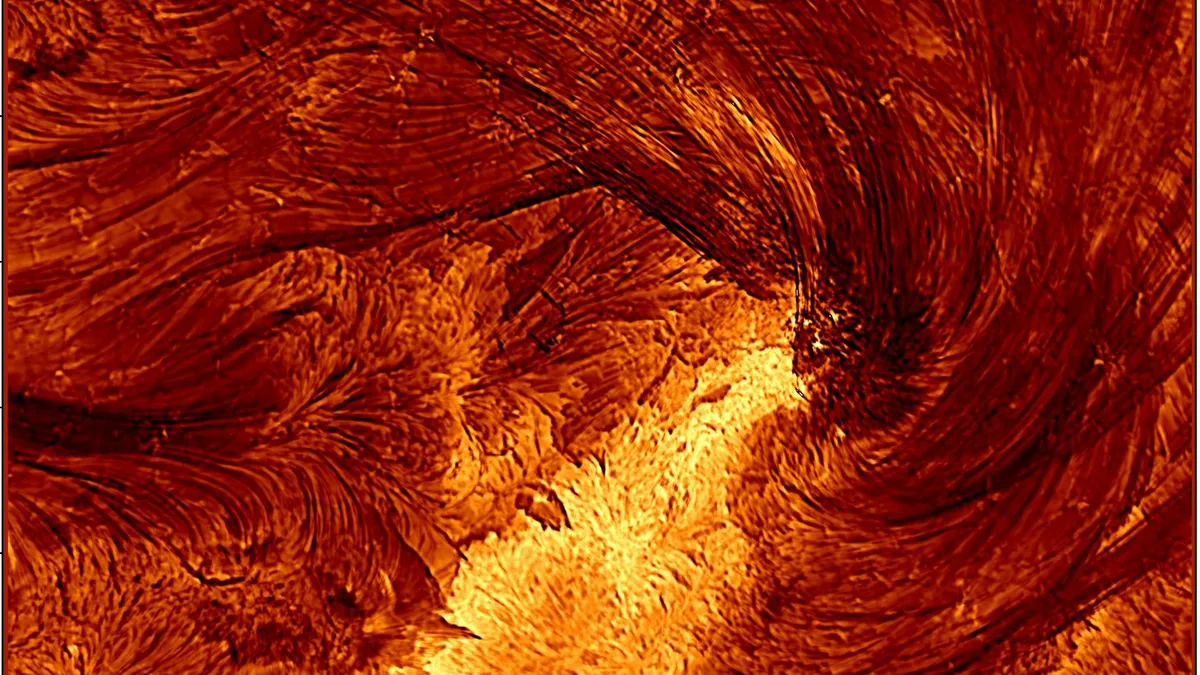

The Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope (DKIST), operated by the NSF's National Solar Observatory, has successfully imaged hundreds of coronal loop strands, with an average width of just 29.95 miles (48.2 kilometers). Some of these loops may be as thin as 13 miles (21 kilometers), pushing the limits of the DKIST's high-resolution capabilities, which are more than 2.5 times sharper than those of the next best solar telescope.

Before the Inouye Solar Telescope's groundbreaking work, scientists could only theorize about the existence of these small loops. Tamburri remarked, "Now we can see it directly." The telescope observed this dense network of loops in hydrogen-alpha light following an X-class flare—the most powerful category of solar flares—on August 8, 2024. This marked the first time the Inouye Solar Telescope has detected an X-class flare, and Tamburri noted that the conditions for observation were optimal.

While the exact role of these small loops in the magnetic reconnection process is still being investigated, their detection allows scientists to integrate their findings into existing models of solar dynamics. If these small coronal loops are indeed fundamental components of the sun's magnetic architecture, it represents a significant advancement in our understanding. Tamburri illustrated this breakthrough by comparing the previous view of a forest of loops to now being able to identify individual trees, stating, "We're not just resolving bundles of loops; we're resolving individual loops for the first time."

The stunning images produced by the Inouye Solar Telescope underscore its capabilities and importance in advancing solar research. Tamburri is supported by the Inouye Solar Telescope Ambassador Program, funded by the NSF, which aims to equip young researchers with the expertise needed to thrive in the broader solar community.

However, concerns loom over the future of the Inouye Solar Telescope. The proposed budget for the fiscal year 2026 by the U.S. government indicates a drastic funding reduction from $30 million to $13 million. Christoph Keller, director of the NSF's National Solar Observatory, warns that this funding shortfall would jeopardize the telescope's operations. The potential closure of the Inouye Solar Telescope would not only result in the loss of its exceptional solar images but also the invaluable training of researchers that could hinder future solar studies for years.

In conclusion, if this marks the Inouye Telescope's final chapter, it certainly concludes on a high note, showcasing the intricate details of our sun like never before.