A decades-long scientific debate regarding the origins of the Silverpit Crater in the southern North Sea has finally been resolved. New evidence confirms that this geological structure was formed by an asteroid or comet impact approximately 43–46 million years ago. A research team led by Dr. Uisdean Nicholson from Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh utilized advanced seismic imaging, microscopic analysis of rock cuttings, and numerical modeling techniques to provide the most compelling evidence to date that Silverpit is one of Earth's rare impact craters. Their groundbreaking findings have been published in the scientific journal Nature Communications.

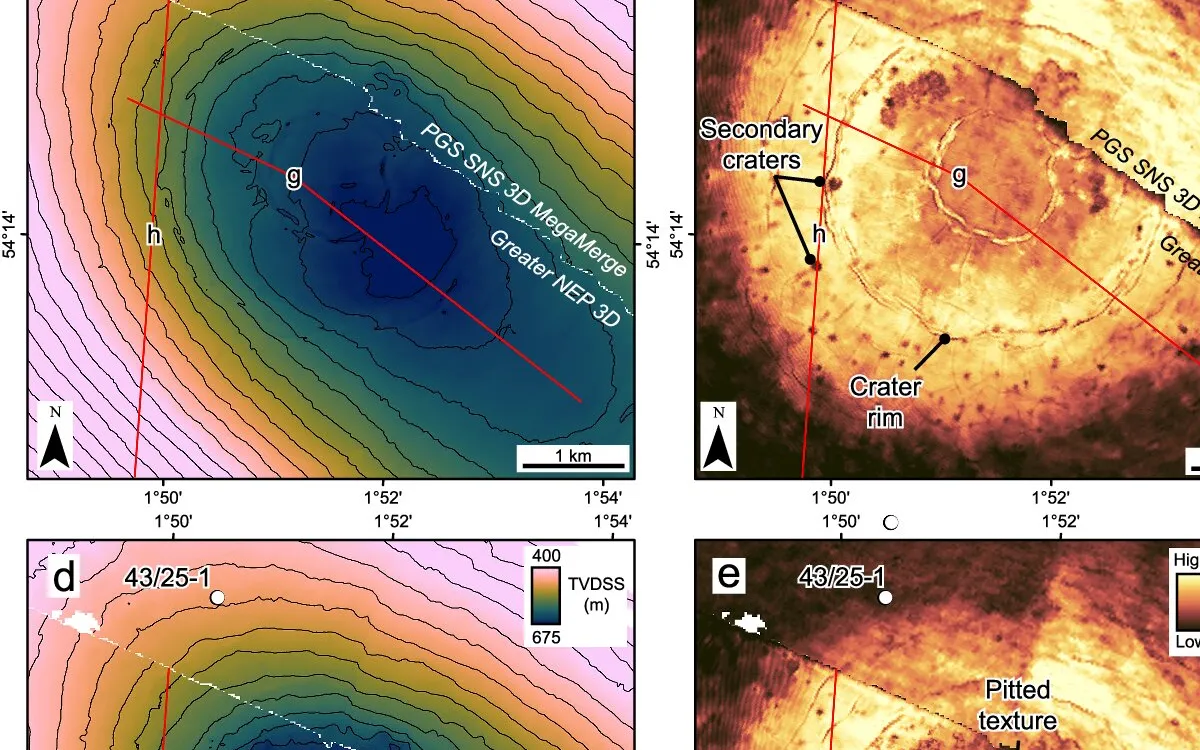

The Silverpit Crater is located 700 meters beneath the seabed of the North Sea, approximately 80 miles off the coast of Yorkshire. Discovered in 2002, this 3 km-wide crater is encircled by a 20 km-wide zone of circular faults, making it a significant site for geological study. Since its discovery, it has been the focus of intense debate among geologists. Initial studies pointed to the crater's distinctive characteristics, such as its central peak, circular shape, and concentric faults, which are commonly associated with hypervelocity impacts.

However, alternative theories emerged, suggesting that the crater's formation could be attributed to other geological processes, such as salt movement deep beneath the crater floor or the collapse of the seabed due to volcanic activity. In 2009, geologists even organized a vote on the crater's origins, as reported in the December issue of Geoscientist magazine, where a majority dismissed the impact hypothesis. Recent findings have overturned this previous consensus.

The team from Heriot-Watt University employed newly available seismic imaging data and evidence collected from below the seabed to substantiate the impact theory. Dr. Nicholson, a sedimentologist in the university's School of Energy, Geoscience, Infrastructure and Society, explained, "New seismic imaging has provided us with an unprecedented view of the crater." Additionally, samples obtained from an oil well in the vicinity revealed rare 'shocked' quartz and feldspar crystals at the same depth as the crater floor. Dr. Nicholson described the discovery as a "real 'needle-in-a-haystack' effort," emphasizing its significance in proving the impact hypothesis due to the unique fabric of the crystals, which can only be formed under extreme shock pressures.

The research indicates that a 160-meter-wide asteroid struck the seabed at a low angle from the west, generating a 1.5-kilometer-high curtain of rock and water that subsequently collapsed into the sea, creating a tsunami that exceeded 100 meters in height.

Professor Gareth Collins from Imperial College London, who was involved in the Silverpit Crater debate in 2009 and contributed the numerical models for the new study, expressed his satisfaction with the findings. "I always believed that the impact hypothesis was the simplest explanation and most consistent with the observations," he stated. "It is very rewarding to have finally found the silver bullet." He added that this new data would allow researchers to explore how impacts shape planetary surfaces, a challenging endeavor for celestial bodies beyond Earth.

Dr. Nicholson emphasized the rarity of the Silverpit Crater, calling it an "exceptionally preserved hypervelocity impact crater." Such craters are uncommon due to Earth's dynamic nature—plate tectonics and erosion typically obliterate most evidence of these events. Currently, there are around 200 confirmed impact craters on land, with only about 33 identified beneath the ocean. The findings from this study provide invaluable insights into how asteroid impacts have influenced Earth's history and can help predict the potential consequences of future asteroid collisions.