The plague, commonly referred to as the Black Death or the Great Pestilence, is a disease that is seldom contracted in today's world. However, it recently made headlines when a resident of South Lake Tahoe was infected. Before you consider donning a 17th-century “air-purifying” beaked mask, let’s delve deeper into why this ancient disease is still present and the level of danger it poses today.

Most individuals associate the term “plague” with the catastrophic event that claimed the lives of approximately 25 million Europeans during the Middle Ages. According to Professor John Swartzberg from UC Berkeley’s School of Public Health, the 14th century plague wiped out nearly 50% of Europe’s population. “The plague is really a specific disease that has ... in our human history reared its ugly head and caused massive deaths,” explains Swartzberg, who specializes in infectious diseases and vaccinology.

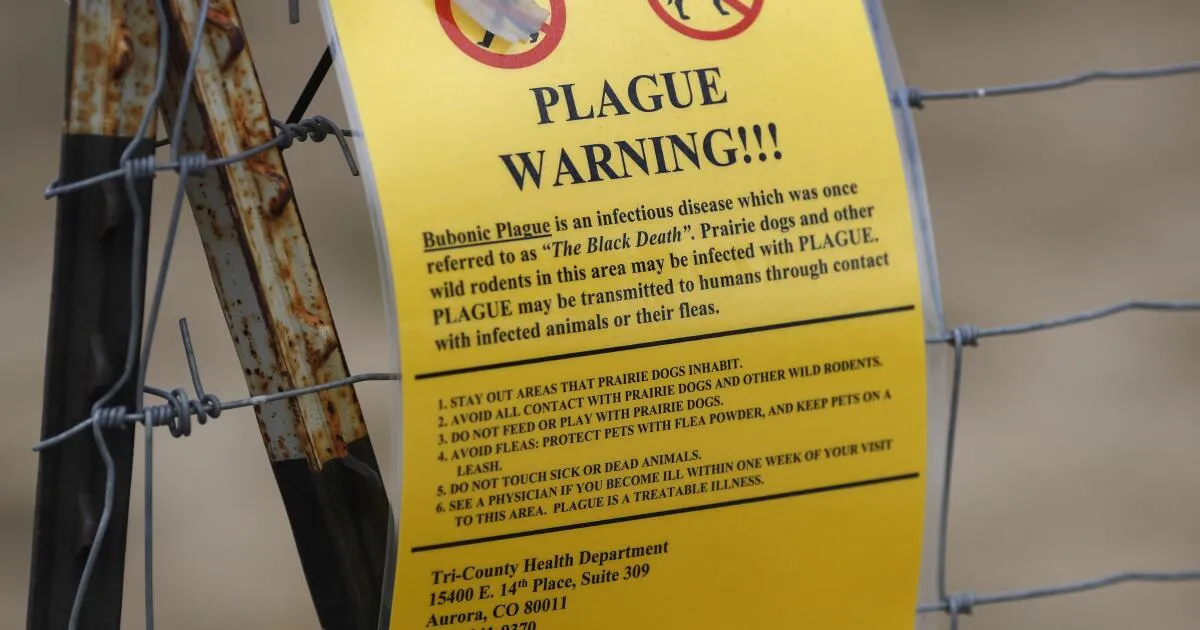

While the plague may seem like a relic of the past, it remains a serious health concern, with a small number of cases reported each year. The recent case involving the South Lake Tahoe resident was attributed to a bite from an infected flea during a camping trip, as noted by health officials in El Dorado County. The last reported case in this area prior to this incident was in 2020, also believed to have been transmitted in the same vicinity. Historical data shows that there were two cases of the plague reported in California in 2015, likely due to bites from infected fleas or rodents in Yosemite National Park.

The plague is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, which primarily affects small animals and rodents in the United States. Swartzberg outlines three types of plague:

Bubonic plague: Characterized by swollen lymph nodes. Septicemic plague: Occurs when the infection spreads throughout the body. Pneumonic plague: Infects the lungs and can be spread through respiratory droplets.Humans and pets can contract the plague through bites from infected fleas or direct contact with infected rodents. The bacterium was introduced to the U.S. in the early 20th century via rat-infested steamships from Asia, with the first case documented in the San Francisco area. Although the last known case of rat-associated plague occurred in Los Angeles in the 1920s, wild rodents in rural areas continue to be the primary source of the disease today.

In California, public health officials indicate that the plague is most commonly found in the foothills, plateaus, mountains, and coastal regions. It is largely absent from the southeastern desert and the Central Valley. The greatest risk of exposure exists in the rural recreational and wilderness areas of the Angeles National Forest and the San Gabriel Mountains. Residents and visitors in close contact with wild rodents are at a higher risk, as are pet owners since dogs and cats can also contract the disease through flea bites.

While the U.S. has successfully eradicated only one human infectious disease—smallpox—through vaccination, there are currently no FDA-approved vaccines for the plague. “We don’t know how to eradicate an infection in a mammalian population that’s spread by a vector like fleas,” Swartzberg explains, emphasizing the ongoing challenge. Despite its presence, the plague is not a top priority for infectious disease experts or public health officials, as it is largely under control.

Experts assert that there is little to fear from the plague if timely treatment is administered. The disease can be effectively treated with antibiotics, but if untreated, it can lead to severe complications or even death. “If the infection is overwhelming,” warns Ashok Chopra, professor of microbiology and immunology, “then the bacteria can spread quickly into the bloodstream, making it very dangerous.”

In conclusion, while the plague may evoke fears of the past, understanding its current implications and maintaining awareness of its potential risks is essential for safety, especially in rural areas where exposure is more likely.