A recent resurgence of measles is alarming health officials across multiple U.S. states, as the number of affected children requiring hospitalization continues to rise. Over the past two months, public health officials have reported a staggering 301 confirmed cases of measles, with more than 170 of these infections concentrated in Gaines County, West Texas. This outbreak has also tragically resulted in the death of a school-aged child, marking the first measles-related death in a child in the U.S. in 22 years. Furthermore, an adult in New Mexico also succumbed to the disease after testing positive for measles, with both individuals being unvaccinated.

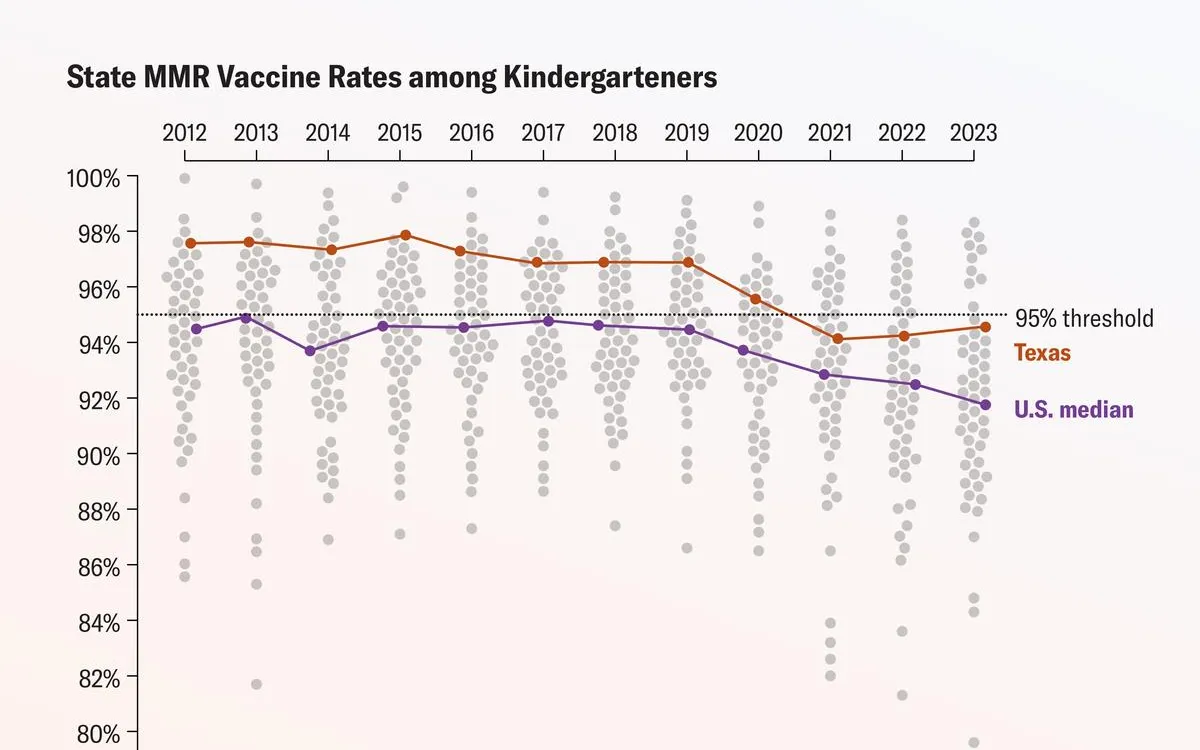

The serious nature and ongoing spread of measles cases have prompted experts to call for a thorough examination of the nation’s childhood vaccination rates, particularly for the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. The MMR vaccine, which requires two doses, is 97 percent effective at preventing measles infection. However, due to the highly contagious nature of the disease, at least 95 percent of a population must be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity. Unfortunately, Texas’s vaccination rate among kindergarteners is slightly below this threshold, currently sitting at 94.3 percent, resulting in rampant measles spread across more than nine counties.

Why does even a small decrease in vaccination rates lead to such significant outbreaks? One reason is that falling below the recommended vaccination coverage allows for outbreaks to occur. Additionally, state-level data may mask local dynamics that are essential for understanding how outbreaks spread. Epidemiologist Emily Smith from George Washington University emphasizes that “what really matters for transmission are the people you see every day.” By analyzing county-level data, health officials can gain insight into the outbreak, but smaller community dynamics often remain overlooked.

In Gaines County, for instance, many initial measles cases originated within a “close-knit, under-vaccinated” Mennonite community. Moreover, the county has a substantial population of homeschooled children not included in school vaccination data, likely leading to a higher number of unvaccinated children than reported.

Texas is one of 45 states that permit nonmedical exemptions, allowing parents to opt out of childhood immunizations for personal or religious reasons. In Gaines County, nearly 20 percent of kindergarten students opted out of at least one vaccine last year, which is five times the national average. This trend highlights the challenges of maintaining adequate vaccination levels in communities.

Measles is significantly more contagious than seasonal influenza. The virus can remain airborne for hours after an infected person coughs or sneezes, making it easy for others to contract the disease without direct contact. The average reproduction number for measles is approximately 15, meaning that one infected person can spread the virus to 15 others. The symptoms of measles typically include high fever, a cough, and a distinctive red rash. Unfortunately, there is no specific treatment for measles, and complications are not uncommon. About one in five unvaccinated individuals who contract the disease will require hospitalization, often due to pneumonia. In Texas, several hospitalized patients, including at least one child under six months old, required intubation.

Measles can lead to severe complications, including death. Approximately one in every 1,000 children infected will die from the disease, and another one in 1,000 may develop acute brain swelling, known as encephalitis, which can occur months after the initial infection and lead to permanent brain damage. A rare complication, subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), can develop years later, resulting in a chronic infection of the brain with devastating outcomes. Dr. Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center, notes that SSPE always leads to death, highlighting the grave risks associated with measles.

As national rates for childhood vaccinations began to decline, pediatricians expressed concern, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic when many children fell behind on routine vaccinations. During the 2019-2020 school year, 95 percent of kindergarteners received all state-mandated vaccines, but this figure dropped to 93 percent in the 2022-2023 school year. While a few states have recovered their vaccination rates since the pandemic, average rates for MMR vaccinations have continued to decrease over the past six years.

Factors contributing to this decline include growing distrust in public health initiatives, exacerbated by figures like Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., who has long promoted anti-vaccine rhetoric. Despite his recent calls for improved accessibility to MMR vaccines, many experts disagree with his claims that the current number of measles outbreaks is “not unusual.” Epidemiologist Emily Smith asserts that this outbreak is atypical due to sustained local transmission and a child’s death in West Texas.

The current measles outbreaks serve as a critical reminder of the importance of herd immunity. As evidenced by a measles outbreak in the Netherlands from 1999 to 2000, unvaccinated individuals were 224 times more likely to contract the disease compared to vaccinated individuals. This paradox highlights that even vaccinated people can be at risk if they are surrounded by unvaccinated clusters, as they face repeated exposure to the virus.

Achieving strong vaccination coverage is vital to preventing the spread of measles and other vaccine-preventable diseases. Dr. Offit emphasizes that herd immunity not only protects vaccinated individuals but also safeguards those who cannot receive the MMR vaccine, such as infants and individuals with compromised immune systems. “There are millions of people who depend on the herd to protect them,” he states.