The parking lot of the Arvo Pärt Center resembles more of a trailhead or campsite than a conventional music institution. Surrounded by a serene sea of Scots pine trees, visitors are greeted by a winding path that curves into the forest, leading them away from the chaos of modern life. On a tranquil evening in July, sunlight filtered through the leaves, illuminating the path as the sounds of traffic faded, replaced by the soothing notes of birdsong. After a short walk, the center emerges: a stunning, wavy white building featuring expansive floor-to-ceiling windows and a tower reminiscent of an abstract steeple. This long trek from the parking lot to the entrance serves as a mental cleansing, urging visitors to reset their minds before stepping into the world of Arvo Pärt, one of the most celebrated classical music composers of our time.

Perched in the tranquil forest on the outskirts of Laulasmaa, Estonia, the Arvo Pärt Center is roughly 45 minutes by car from Tallinn, the nearest major city. Its isolation creates a temple-like atmosphere, emphasizing spirituality as a core element of the experience. Within the center lies a courtyard featuring a chapel that Pärt, who resides nearby, frequents regularly. The library at the center is home to Pärt's extensive collection of religious texts, embodying the ethos of a composer whose music demands both love and dedication from its interpreters, while offering an accessible, timeless sound that resonates with both casual listeners and avant-garde enthusiasts alike.

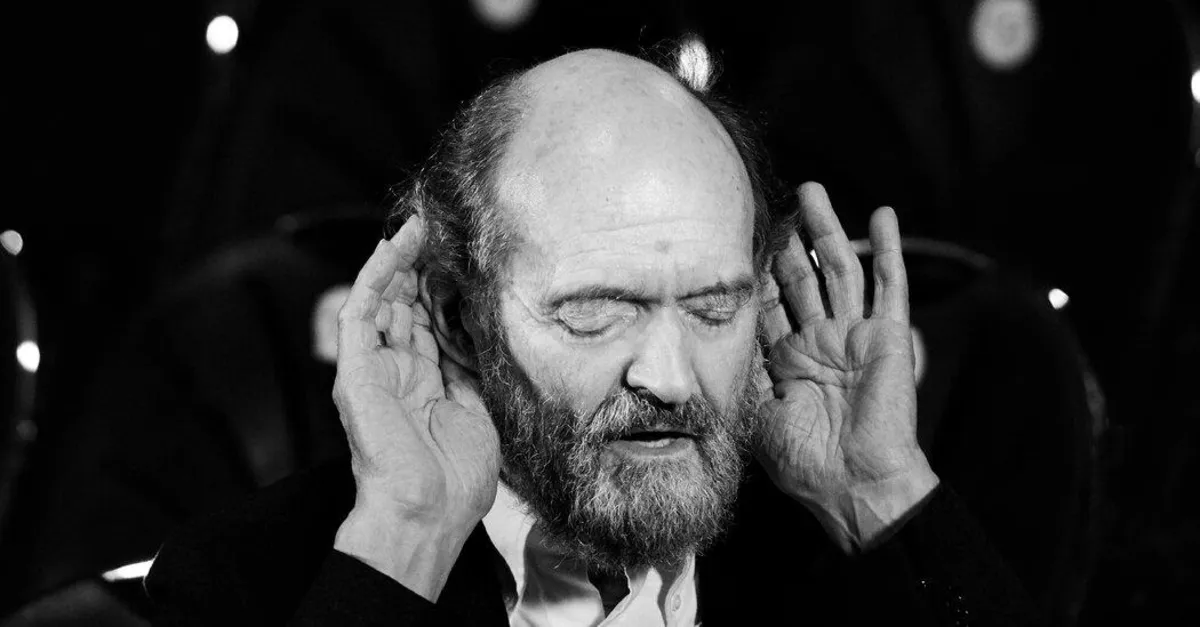

Arvo Pärt is revered in circles typically reserved for pop stars, with prominent musicians expressing their admiration for his work. Michael Stipe has described Pärt's music as “a house on fire in an infinite calm,” while PJ Harvey shared that she can only handle the profound experience of “Tabula Rasa” once a year. Thom Yorke eloquently articulated the transformative experience of listening to Pärt's compositions, likening it to discovering a hidden world. Clive Gillinson, Carnegie's executive and artistic director, has stated, “He’s one of the great composers of our day,” highlighting Pärt's extraordinary popularity and his ability to resonate deeply with the cultural zeitgeist.

Pärt's catalog of works is largely complete, yet it is performed with increasing frequency by new and younger artists. He has achieved a remarkable feat by inventing a unique system of composing known as tintinnabuli, a method that has attracted an unprecedented number of listeners to classical music. Paul Hillier, whose ensemble set a high standard for performing Pärt's works, remarked, “It’s great music, it’s as simple as that.” Pärt's early influences included Shostakovich and Prokofiev, but he soon veered away from serialism, experimenting with a collage technique that melded early music, such as Gregorian chant, with modern dissonance.

In 1968, Pärt took a significant turn towards the spiritual with his work “Credo,” aligning him with composers like Sofia Gubaidulina and Henryk Gorecki. However, this spiritual exploration led to a period of quietude, during which he joined the Russian Orthodox Church and filled notebooks with drawings and sketches inspired by plainchant. This journey culminated in 1976 with the creation of “Für Alina,” a minimalist piano solo that served as a prototype for his tintinnabuli style. The score reflects a modern interpretation of Renaissance music, featuring notes without stems and no strict rhythmic structure, allowing the performer complete freedom in tempo and expression.

As a result of increasing tensions in Estonia, Pärt and his family emigrated, initially intending to go to Israel due to his wife Nora's Jewish background. However, they ultimately settled in Vienna, where Pärt received a publishing contract that provided him with a refuge. Later, they moved to Berlin, where they remained for nearly three decades. It was during this time that Pärt caught the attention of Manfred Eicher, founder of ECM Records, who established the ECM New Series specifically to release Pärt's breakthrough album, “Tabula Rasa,” in 1984, catapulting him to global acclaim.

Pärt's music holds a unique mystery, resonating with audiences regardless of their familiarity with classical music. Critics and fans alike have noted its broad spiritual appeal, drawing on elements from various religions. His harmonic language transcends time, feeling equally at home in both the 15th and 21st centuries. Michael Pärt describes his father's music as “without boundaries,” a sound that is both personal and devotional, reflecting Pärt’s belief that art should engage with the eternal rather than merely the immediate.

Despite its accessibility, Pärt's music poses significant challenges for performers. He has stated that “it is enough when a single note is beautifully played,” yet the fragility of his compositions can be difficult to sustain. Interpreters often describe the need for selflessness and a deep understanding of the music's essence. As Hillier notes, “We don’t want to hear the performer perform; just doing the music is enough.” This principle extends to conductors as well, with Michael Pärt observing that his father's scores “pretty much perform themselves,” emphasizing the natural dynamics embedded within the architecture of each piece.

Once considered niche, Arvo Pärt's music has now become integrated into the repertoire of conservatories and concert halls worldwide. Since returning to Estonia in 2010 as a national treasure, his influence has only grown. The Arvo Pärt Center, established in 2018, serves as a vital resource for anyone interested in his music. Recently, young members of the Järvi Academy performed Pärt’s “Greater Antiphons” at the center, showcasing not only technical skill but also the profound beauty that characterizes his timeless compositions.