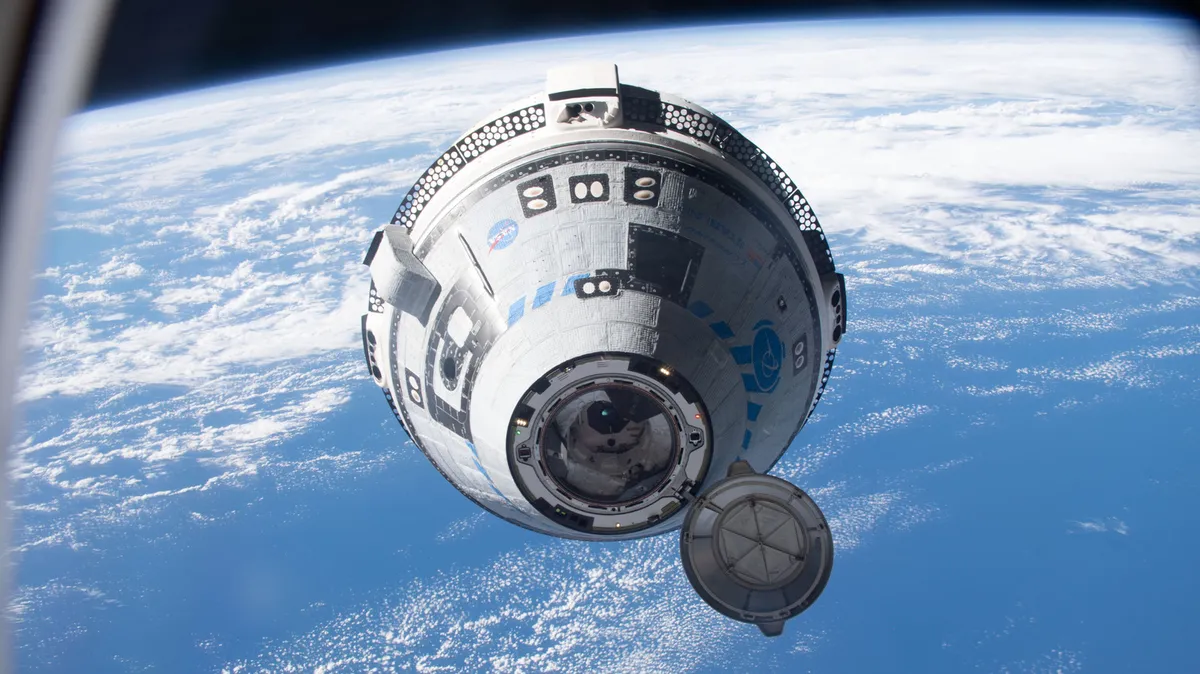

In June, NASA faced significant challenges with the problematic Boeing Starliner during its Crew Test Flight. Despite NASA's attempts to publicly downplay the situation, the reality was far more serious for the astronauts at the controls and the mission control team. Astronaut Butch Wilmore revealed that the Starliner experienced multiple thruster failures, leading to a loss of full control during its launch rendezvous with the International Space Station (ISS).

The situation was critical enough that it should have mandated an abort of the docking attempt; however, NASA chose to waive established flight rules. The astronauts aboard the Starliner had an uneasy feeling about potential complications, especially after witnessing thruster failures during previous uncrewed Orbital Flight Test missions. Initially, the launch proceeded smoothly, with the ULA Atlas V rocket maintaining its trajectory perfectly and the Starliner excelling in post-separation maneuvering tests.

As the Starliner approached the ISS, it encountered severe issues with its thrusters. Wilmore had to take manual control of the spacecraft after two thrusters failed. He emphasized the gravity of the situation, stating that a third failure would result in losing control over the spacecraft's six degrees of freedom (6DOF), which are essential for maneuvering in three-dimensional space. Despite standard procedures suggesting an abort in such situations, NASA opted to continue the mission, leading to further complications when two additional thrusters failed.

In an interview with Ars Technica, Wilmore expressed his gratitude towards NASA's Mission Control in Houston, calling them heroes for their adept management of the crisis. With the loss of forward control, the Starliner was trapped in a situation where it could neither dock with the ISS nor position itself for reentry into Earth's atmosphere. This precarious condition highlighted the risks involved in space missions.

Under the guidance of Mission Control, Wilmore had to relinquish control of the spacecraft so that flight controllers could attempt a reset of the thrusters remotely. Fortunately, this maneuver successfully restored functionality to two of the failed thrusters, allowing the Starliner to regain control and complete the docking process with the ISS.

While the crew was safe aboard the ISS, they found themselves effectively stranded, unable to pilot the spacecraft back home. In a worst-case scenario, they could have relied on other docked vehicles for an emergency return. However, they ultimately had to wait for the ISS's crew rotation missions to bring them back. The Starliner made its return empty in September, while the crew remained on the ISS for a nine-month stay, eventually returning with NASA's SpaceX Crew 9 mission in March.

This incident underscores the complexities and risks associated with space travel, particularly with new spacecraft like the Boeing Starliner. As NASA continues to refine its approach, the lessons learned from this mission will undoubtedly shape future operations in the realm of human spaceflight.