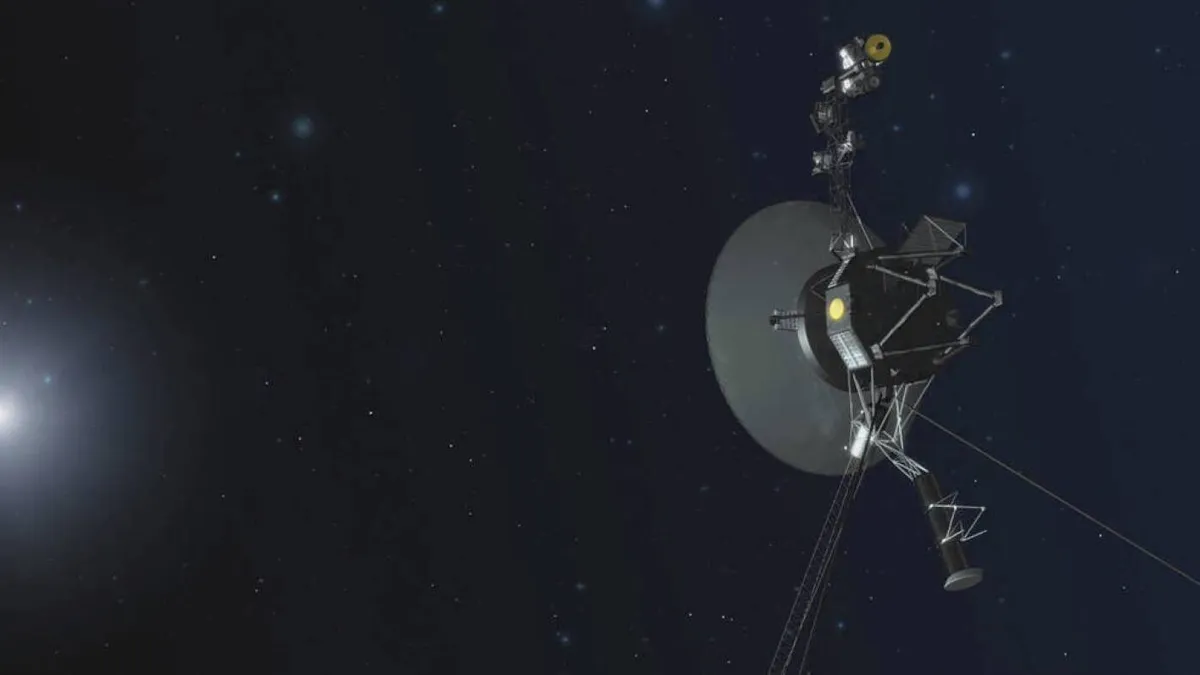

Earlier this year, NASA mission controllers encountered a significant challenge that could have potentially brought an end to Voyager 1's remarkable journey, which has spanned several decades. Launched in 1977, Voyager 1 was designed to explore the outer solar system, operating alongside its twin, Voyager 2. Communication with these spacecraft relies heavily on a powerful ground-based radio antenna, which needed to be temporarily taken offline for essential upgrades. However, there was a legitimate concern that once the antenna was reactivated, contact with Voyager 1 might be irretrievably lost.

The crux of the issue revolved around the spacecraft's roll thrusters, which are critical for maintaining the alignment of its antenna towards Earth. Since 2004, Voyager 1 has relied on its backup thrusters after the failure of the primary system. Unfortunately, signs of impending failure were emerging in the backup system as well. A dangerous buildup of residue in a fuel line posed a risk of completely incapacitating the backup thrusters. Voyager Mission Manager Kareem Badaruddin likened this situation to a nozzle gradually becoming smaller due to debris accumulation, stating, "The thruster gets weaker and weaker and allows less propulsion." This propulsion is crucial; even a minor misalignment of the antenna could sever communication between Voyager 1 and Earth.

According to Patrick Koehn, a program scientist with the Voyager team, "Even just a very small tip away, you know, a fraction of a degree, can swing the beam away from the Earth." He explained that a misalignment of just half a degree could result in the communication beam missing Earth by an extensive distance, comparable to the distance between the Earth and the Sun. The switch to the backup thrusters was prompted by controllers noticing that heater switches in the primary system had turned off unexpectedly, indicating a potential fault.

As options dwindled, engineers revisited the possibility of reviving the primary roll thrusters. They meticulously reviewed old records and ultimately decided to attempt reactivating the heaters on the primary thrusters. "They went back, they looked at the old records. They decided it was worth trying to turn the heaters back on," Koehn remarked. However, the clock was ticking, as Deep Space Station 43, a 230-foot dish located in Canberra, Australia, was scheduled to go offline for upgrades on May 4. This station is the only one capable of sending commands to both Voyager spacecraft and would remain non-operational until February of the following year, with only brief operational periods in August and December.

The Voyager team suspected that the heaters had deactivated due to an electronics glitch. However, there was also a significant risk that attempting to restart the primary thrusters could lead to a catastrophic explosion, as Badaruddin explained. To mitigate this risk, engineers needed to test the thruster without igniting it first, to avoid any disastrous outcomes. Concerns grew that, after being inactive for two decades in the frigid environment of space, the thrusters might be irreparably damaged.

On March 20, the Voyager team received promising news: the test of the primary roll thruster was successful. Despite signs of aging in both spacecraft, the team remains hopeful. In 2023, Voyager 1 had faced issues such as sending garbled data from deep space, but that problem was resolved. Additionally, a glitch in Voyager 2 caused it to momentarily misalign its antenna away from Earth. The Voyager team is optimistic about keeping both spacecraft operational long enough to celebrate their 50th anniversary in 2027. Koehn stated, "There's no reason it wouldn't go past 2027… especially now that we know the thrusters are in good shape."

The Voyager missions represent a remarkable achievement in the field of robotic exploration. According to Matt Shindell, the space history curator at the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum, "That's a unique lifespan in the history of robotic exploration of the planets." The insights gained from these missions continue to benefit scientists today, as they provide the best data available for the outer planets, especially Uranus and Neptune, where the Voyager probes have yielded unparalleled information.

The fact that Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 are still operational and transmitting data is nothing short of extraordinary. As Koehn noted, "The Voyagers are the only man-made objects that can tell us what the space between the stars is really like." The ongoing research from these probes, particularly regarding phenomena such as coronal mass ejections (CMEs), allows scientists to better understand solar activity at vast distances, showcasing the enduring value of the Voyager missions in the realm of space exploration.