In a remarkable study, researchers have successfully disrupted a key gene in chickens, leading to feathers that exhibit more primitive characteristics resembling those of early dinosaurs. This groundbreaking research focuses on the evolutionary origins of feathers, specifically how simple tube-shaped proto-feathers first emerged from the ancestors of dinosaurs during the Early Triassic period, around 250 million years ago.

The study, conducted by a team from the University of Geneva, involved inhibiting the Sonic Hedgehog gene during the embryonic development of chickens. The results were noteworthy but temporary. While the chickens initially displayed delayed feather development and some areas lacking feathers at hatching, their plumage reverted to typical chicken feathers within a few weeks after birth.

Professor Michel Milinkovitch, the senior author of the study, remarked, "Our experiments show that while a transient disturbance in the development of foot scales can permanently turn them into feathers, it is much harder to permanently disrupt feather development itself." This finding highlights the resilience of the genetic network responsible for feather development, which has evolved to withstand significant genetic and environmental changes.

Although the researchers did not achieve permanent dinosaur-like feathers in chickens, the study was far from a failure. Alongside co-author Rory Cooper, now a research fellow at the University of Sheffield, Milinkovitch emphasized the importance of the Sonic Hedgehog gene in feather evolution. By temporarily disturbing this gene, they were able to gain insights into how feathers originally developed.

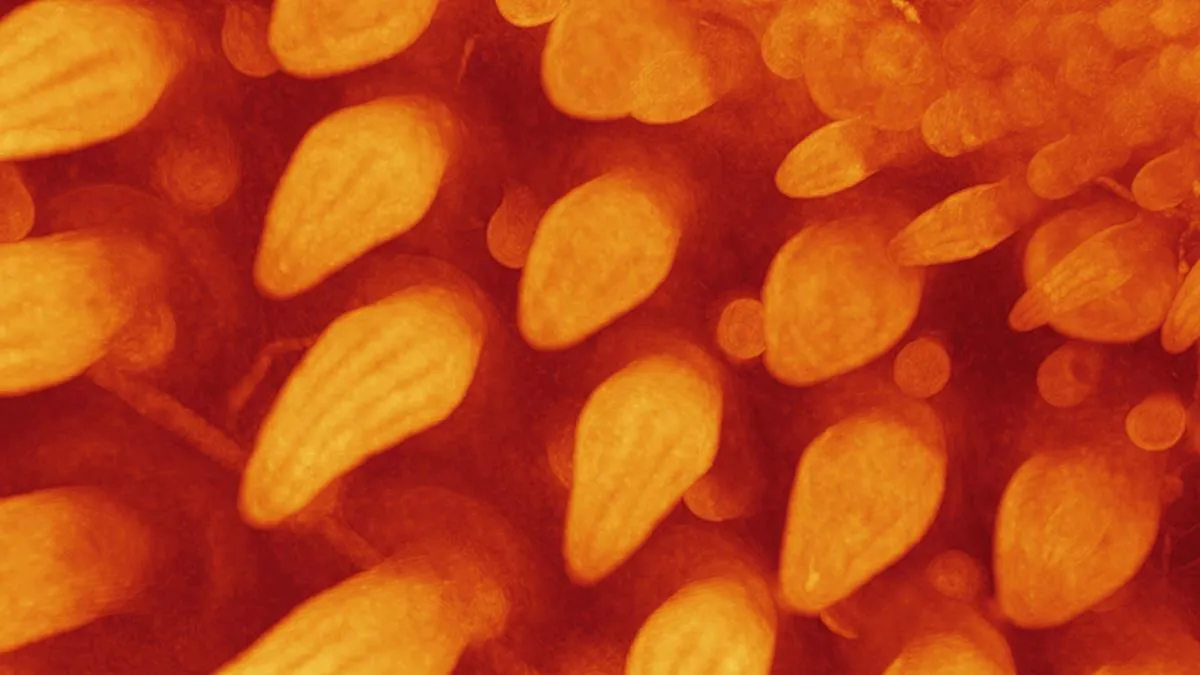

The earliest feathers were not the complex, branching structures seen on modern birds. Instead, they were simple, single tubules resembling tiny drinking straws. To better understand the evolution of feathers, from these primitive forms to the elaborate structures we observe today, the researchers employed a technique called light sheet fluorescence microscopy. This advanced imaging method utilizes lasers to capture thin slices of samples, enabling detailed observations of feather development within chicken embryos.

The study revealed that feather development begins in embryonic chickens approximately nine days after the egg is laid. Initially, thick spots known as placodes emerge across the developing chicken's body. These placodes then develop into feather buds, which eventually transition into the familiar branched feather structure, aided by keratin, a protein also found in human hair and nails.

On the ninth day of development, the researchers injected an inhibitor of the Sonic Hedgehog gene into the eggs. This intervention stunted feather bud growth and hindered the complex branching patterns typical of mature feathers. However, by the 17th day of development, the feather growth showed signs of recovery as the inhibition effect diminished.

Chickens that hatched from these modified eggs exhibited patchy feathers, characterized by some naked spots and areas where soft, down-like feathers had formed. Notably, they lacked the mature outer feathers with a central rachis, the distinctive quill structure found in fully developed feathers. By day 49, however, these chickens underwent molting, and their new feathers developed normally.

The findings, published on March 19 in the journal PLOS Biology, indicate that the Sonic Hedgehog gene plays a significant role in both the evolution of proto-feathers and the diversification of feather types across various species. Moving forward, Milinkovitch expressed the challenge of understanding how genetic interactions have evolved to facilitate the emergence of proto-feathers early in the evolutionary history of dinosaurs.