Recent research suggests that there may be a hidden ocean's worth of liquid water beneath the surface of Mars, supported by seismic evidence. A new study published on April 25 in the National Science Review highlights recordings of seismic waves that indicate the presence of a layer of liquid water trapped in Martian rocks, lying between 3.4 and 5 miles (5.4 to 8 kilometers) below the surface. The researchers estimate that the total volume of this hidden water could potentially flood the entire Martian surface with an ocean measuring between 1,700 and 2,560 feet (520 to 780 meters) deep, comparable to the amount of liquid contained within Antarctica's ice sheet.

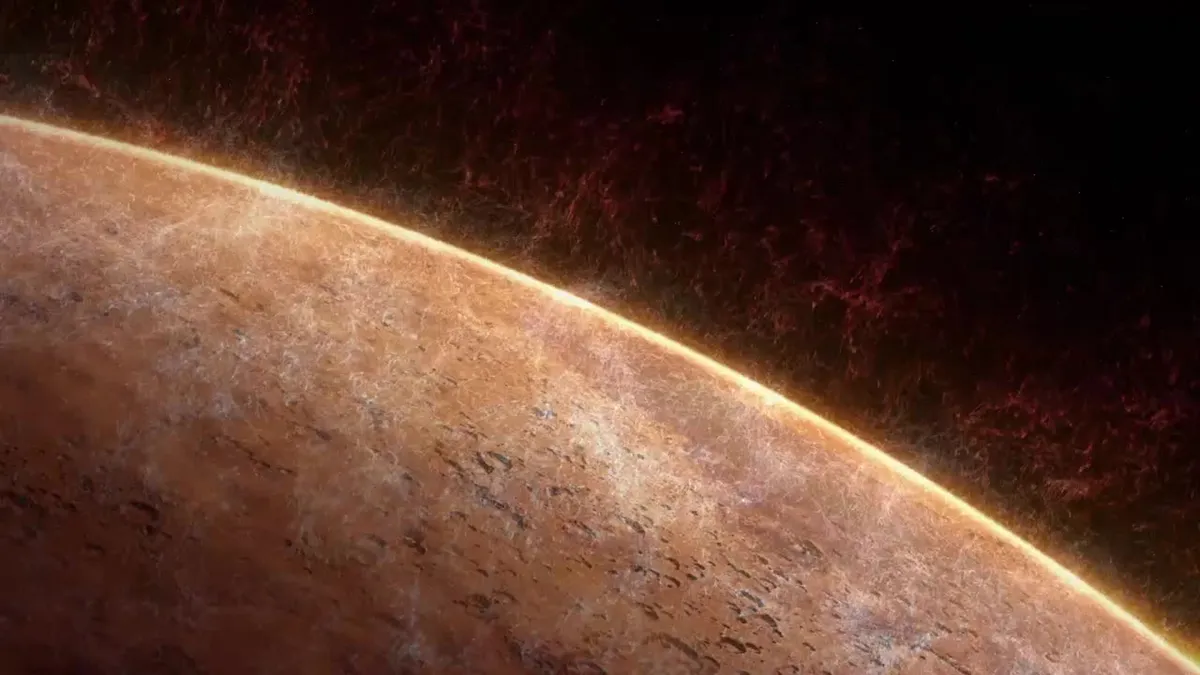

Mars was once home to abundant liquid water, particularly during the period between its formation approximately 4.1 billion years ago and around 3 billion years ago. Evidence of this ancient water is evident in the planet's geological features, such as valley networks, delta formations, and layered sedimentary rocks, all of which suggest sustained water flow. However, this once plentiful liquid water has since disappeared, leaving behind the cold, dry environment we observe today. According to Hrvoje Tkalčić, a professor of geophysics at the Australian National University and co-author of the study, the transition to this arid state occurred as Mars lost its magnetic field and its atmosphere was gradually stripped away by solar radiation.

As the atmosphere thinned, Mars experienced a drop in surface temperatures, leading to a loss of liquid water. The water either escaped into space, became trapped as ice in the subsurface or polar caps, or integrated into hydrated minerals within the crust. Despite these findings, researchers have long been puzzled by the significant volume of water that appears to be unaccounted for, raising questions about whether there remains liquid water hidden beneath the Martian surface.

The latest research provides compelling evidence that there may indeed be liquid water buried deep within Mars. By analyzing seismic data collected by NASA's InSight lander, which has been operational on Mars since 2018, the researchers discovered that seismic waves slowed down between 3.4 and 5 miles (5.4 to 8 kilometers) below the surface. This slowdown is likely indicative of liquid water present in porous rocks, as seismic waves travel more slowly through liquids compared to solid materials. Tkalčić and co-author Weijia Sun, a professor of geophysics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, liken this low-velocity layer to a saturated sponge, akin to Earth's aquifers where groundwater seeps into rock pores.

The researchers propose that this liquid water could account for the significant volume of water that previous studies have deemed "missing." Tkalčić emphasized that much of the ancient water may have percolated through the porous surface rocks and remained underground, aligning with estimates of unaccounted water from other research. Furthermore, prior studies have indicated that substantial quantities of water could be stored beneath the Martian surface in ice form, with some estimates suggesting the presence of liquid water within rocks located 7 to 13 miles (11.2 to 21 km) beneath the surface.

The potential existence of liquid water on Mars excites scientists, as the presence of liquid water is crucial for life as we understand it. These hidden reservoirs could potentially harbor some form of Martian life. However, confirmation of this liquid water will require deeper exploration, including drilling missions to access these depths and directly investigate the Martian subsurface. Tkalčić emphasizes the need for future missions equipped with seismometers and drills to validate the findings and gather further insights into the existence of water on Mars.