Recent research led by the Ocean Discovery League has unveiled a startling revelation: humans have explored less than 0.001 percent of the deep seafloor, a vast area covering two-thirds of our planet. This groundbreaking finding emphasizes the limited understanding we have of life and geological processes occurring below depths of 200 meters. The study utilized data from approximately 44,000 deep-sea dives conducted since 1958, producing the first global estimate of visual coverage in these profound waters. The researchers concluded that the total area imaged is comparable to the size of the U.S. state of Rhode Island.

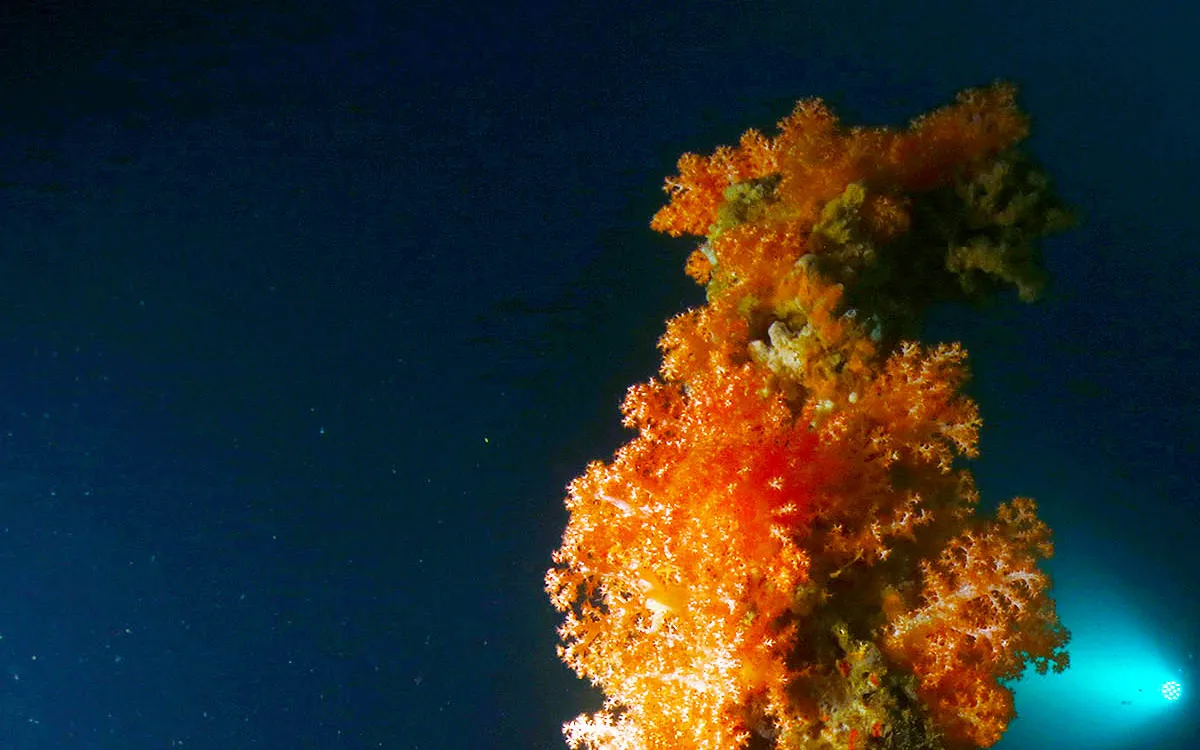

The deep ocean is home to rich ecosystems, plays a critical role in moderating the climate, generates a significant portion of Earth's oxygen, and provides essential molecules for developing new drugs. Despite its importance, visual surveys of this underwater realm are infrequent and primarily concentrated near a few coastlines. This limitation arises mainly because expeditions to explore the deep sea can cost millions of dollars. According to lead author Katy Croff Bell, founder and president of the Ocean Discovery League, “As we face accelerated threats to the deep ocean – from climate change to potential mining and resource exploitation – our limited exploration of such a vast region presents a critical challenge for both science and policy.”

The study reveals that approximately 65 percent of all visual observations have occurred within 200 nautical miles of just three countries: the United States, Japan, and New Zealand, which dominate the field due to their ownership or funding of most deep-diving vehicles. In total, only five nations – the United States, Japan, New Zealand, France, and Germany – have conducted ninety-seven percent of all recorded dives, leading to a skewed understanding of the deep sea. The environments observed off the coasts of California or Honshu may not accurately represent conditions in the tropical Atlantic or the Southern Ocean.

Notably, nearly 30 percent of the dives documented in the study took place before 1980, producing primarily black-and-white photographs. While contemporary color and video technology can reveal minute organisms and articulate sediment patterns, large portions of the ocean floor have yet to be filmed with modern equipment. The researchers assessed how the absence of comprehensive records might influence their estimates. Even if the actual number of dives were ten times higher, they concluded that we would still possess images representing less than one-hundredth of one percent of the deep seafloor.

Features such as canyons and ridges attract researchers due to their visual appeal and the potential for hosting rare species. In contrast, the expansive abyssal plains and numerous seamounts remain largely unexamined. Although these plains constitute the majority of the deep ocean floor, they continue to be poorly sampled. Without accurate data, scientists struggle to assess the impacts of global warming, fishing gear, and planned seabed mining on these vast habitats. The authors argue that financial constraints, rather than a lack of curiosity, hinder exploration efforts. Deep-rated submersibles, remotely operated vehicles, and large research vessels require substantial funding.

Encouragingly, technologists are developing smaller, more affordable robots and camera sleds that coastal laboratories can utilize. These innovations could facilitate exploration in low- and middle-income nations, allowing them to gather images from their own waters and contribute to a more comprehensive global map. Ian Miller of the National Geographic Society emphasized the importance of deep-sea exploration, stating, “Dr. Bell’s goals to equip global coastal communities with cutting-edge research and technology will ensure a more representative analysis of the deep sea.”

The stark comparison made in the paper illustrates the limitations of our current understanding: attempting to grasp the entirety of land life on Earth while only studying an area the size of Houston, Texas mirrors our visual knowledge of the deep sea. Without broader exploration, global policies concerning deep-sea mining, fishing, and climate mitigation rely on dangerously limited data. The authors advocate for agencies, foundations, and industries to support large-scale imaging campaigns and encourage researchers to share dive records openly. This collaborative approach would allow every frame of footage and still image to contribute to a collective archive, enabling analysts worldwide to identify new species, map coral gardens, or track drifting debris in deep-sea trenches.

Advancements in technology provide a glimmer of hope for future explorations. Autonomous vehicles that can fit in a suitcase are capable of diving thousands of meters, while machine learning algorithms can process extensive deep-seafloor footage in mere minutes. Additionally, fiber-optic cables laid on the seabed can detect passing marine life through minute pressure changes. Collectively, these innovations could exponentially increase visual coverage within the next decade. This study marks a pivotal moment in how society perceives the hidden majority of our planet, illuminating existing gaps and establishing clear targets for future research. Addressing these gaps will necessitate funding, new technologies, and global collaboration, but the potential rewards are immense, including improved climate forecasts, novel medicines, and the exhilarating prospect of discovery in previously unexplored regions. The full study is available in the journal Science Advances.

—– Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates. Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com. —–