Recent research has revealed an astonishing fact: we possess better visuals of Mars than we do of our own ocean floor, and the margin is wider than many might assume. A comprehensive study published in Science Advances analyzed data from an impressive 43,681 deep-sea dives conducted since 1958, leading to a shocking conclusion: only 0.001% of the deep seafloor has been visually observed. To put this into perspective, this area is slightly larger than the state of Rhode Island or roughly one-tenth the size of Belgium, all while covering about 70% of our planet.

The average depth of the ocean is approximately 12,080 feet (3,682 meters), making visual observation a daunting task unless one possesses the abilities of Aquaman or utilizes advanced deep-sea submersibles. As of June 2024, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reports that only 26.1% of the global seafloor has been mapped. However, achieving visual observation represents a more significant challenge. Susan Poulton, a researcher at the Ocean Discovery League and co-author of the study, stated in an email to Gizmodo that, “This small and biased sample is problematic when attempting to characterize, understand, and manage a global ocean.”

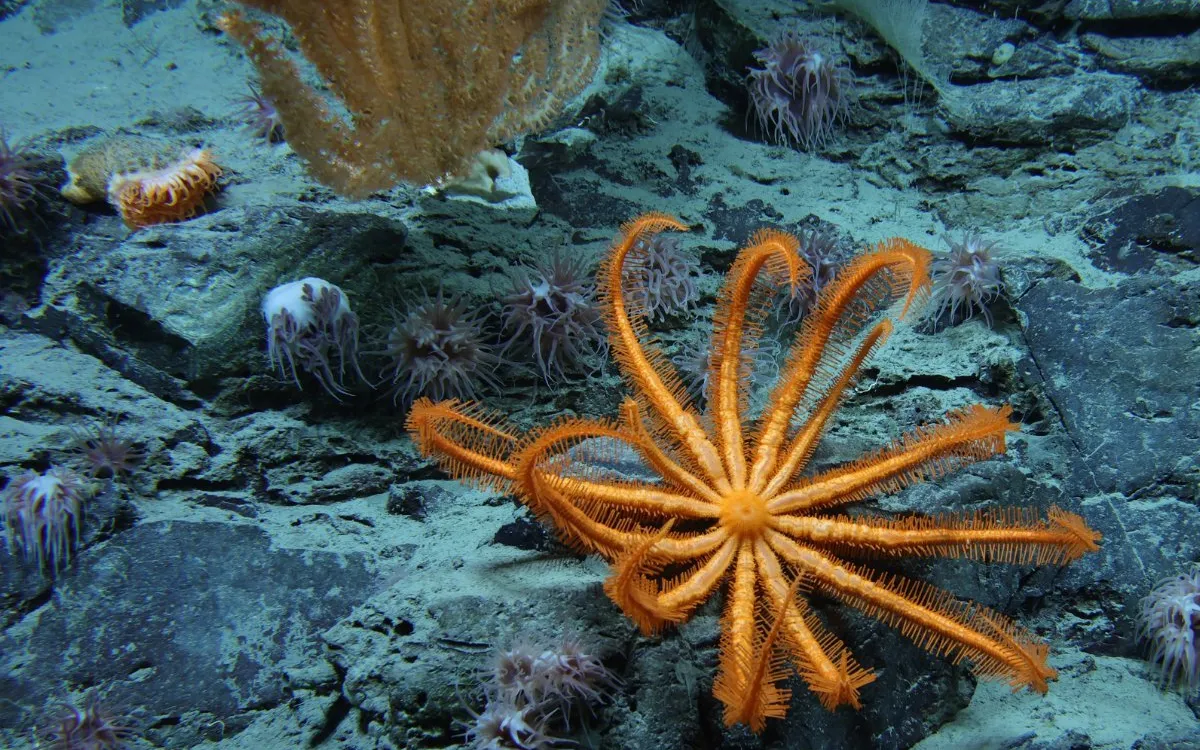

According to NOAA, scientists estimate that two-thirds of the 700,000 to 1,000,000 species in the ocean (excluding microorganisms) remain undiscovered or officially described. This statistic underscores the vast potential for new research in the largely unexplored regions of the deep seafloor. Alarmingly, nearly two-thirds of all visual seafloor observations have occurred within 200 nautical miles of just three countries: the United States, Japan, and New Zealand. Moreover, the majority of deep-sea dives have been conducted by institutions from only five nations: the aforementioned three, along with France and Germany.

Poulton likened the situation to trying to represent critical environments like the African savanna or the Amazon rainforest using solely satellite imagery and DNA samples, without ever witnessing the flora and fauna that inhabit them. “It wouldn’t paint a very complete picture,” she emphasized. The study also identified a significant bias toward sampling in shallow waters (less than 6,562 feet deep or 2,000 meters), despite the fact that nearly three-quarters of the seafloor lies at greater depths. Features like canyons and escarpments receive much attention, while extensive regions of undersea ridges and plains remain largely ignored.

The research team argues that we owe it to ourselves to gain a deeper understanding of these expansive areas of the deep sea. The deep ocean is essential for various global functions, including climate regulation, oxygen production, and even medicinal discoveries. Yet, our visual assessment of these regions represents a mere fraction of what exists. We are missing crucial information regarding not only the creatures inhabiting these zones but also how these ecosystems contribute to Earth's broader processes.

Some significant discoveries in the deep sea have emerged from commercial interests, particularly in regions like the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, which has attracted attention for deep-sea mining. This interest has led to the identification of hundreds of new species and insights into new mechanisms of oxygen production, which might have gone unnoticed if not for the mining exploration. The team's findings come as the Trump Administration has expedited deep-sea mining, raising concerns about the potential threats to the species that inhabit the seafloor and midwater ecosystems.

In the past six months, two research teams uncovered evidence of organisms thriving beneath the seafloor, pushing the boundaries of where we know life exists. However, the push for deep-sea mining threatens to probe these understudied areas, potentially endangering species before scientists even have the chance to identify them. The study highlights the urgency for more nations, institutions, and advanced tools to enhance our exploration of the deep ocean.

With the current pace of exploration, the team estimates it could take over 100,000 years to visually explore the deep seafloor. They advocate for a “fundamental change in how we explore and study the global deep ocean,” as stated in an AAAS press release. Presently, we are making critical decisions regarding global ocean policy, climate change, and biodiversity assessments based on an alarmingly small sample size. It is in the best interest of science—and the thrill of discovery—to innovate and scale our efforts to explore the most elusive and least understood regions of our world.