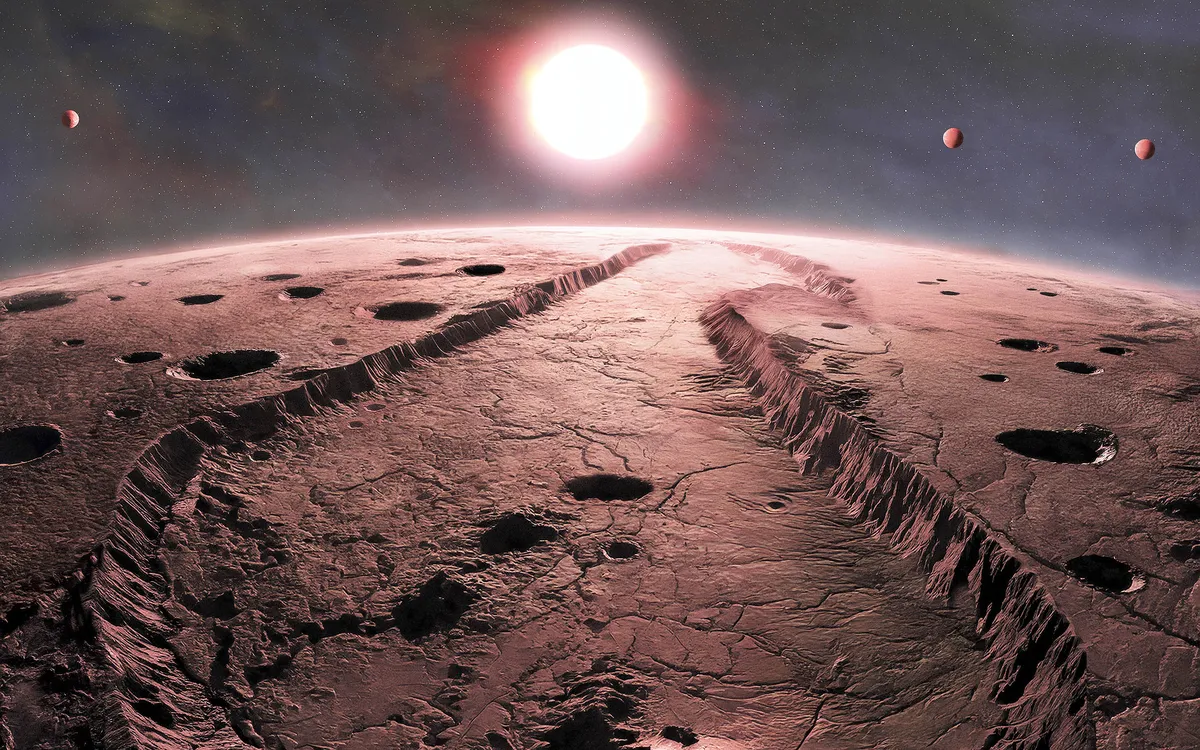

Barnard’s Star has been a focal point for astronomers and those interested in exoplanets beyond our solar system for many years. Located approximately six light-years from Earth, this star is notable for its rapid movement across the night sky. Scientists have long speculated about the possibility of planets in orbit around Barnard’s Star that could provide insight into the formation of planetary systems. Recent observations have revealed promising results—indicating the existence of four miniature planets orbiting this intriguing star.

Recent studies suggest that each of these newfound planets has a mass ranging from 20 to 30% that of Earth and completes an orbit around Barnard’s Star in just a few days. This significant discovery has garnered widespread attention, highlighting advancements in the precision of detecting smaller, elusive planets. “It’s a really exciting find—Barnard’s Star is our cosmic neighbor, and yet we know so little about it,” remarked Ritvik Basant, a Ph.D. student at the University of Chicago and lead author of the study. He emphasized that this breakthrough showcases the enhanced capabilities of new astronomical instruments compared to those of previous generations.

Barnard’s Star was first identified in 1916 by astronomer E. E. Barnard at the Yerkes Observatory. Since its discovery, it has captivated scientists who have often referred to it as the “great white whale” of astronomy. This nickname stems from the numerous claims of potential planets that, over the years, turned out to be unsubstantiated. The latest findings were published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters on March 11, marking a pivotal moment in the ongoing exploration of this star.

Previous observations of Barnard’s Star relied on less sensitive technology, which sometimes resulted in conflicting signals, leading to its legendary status among planet hunters. Experts note that Barnard’s Star is the closest single-star system to our Sun, unlike Proxima Centauri, which is part of a three-star system. This distinction is crucial, as multiple stars can complicate planetary formation, making Barnard’s Star a more favorable candidate for studying solitary planet systems.

Detecting small planets near bright stars can be challenging since they are not easily visible. Instead, astronomers track the subtle gravitational influence these planets have on their host star. The specialized instrument MAROON-X, located at the Gemini Telescope in Hawaii, is capable of detecting slight variations in a star’s light caused by the gravitational pull of orbiting planets. Using this technique, the research team confirmed the presence of three planets around Barnard’s Star. The fourth planet was identified by combining their data with earlier observations made using the ESPRESSO instrument in Chile.

“We observed at different times of night on different days. They’re in Chile; we’re in Hawaii. Our teams didn’t coordinate with each other at all,” Basant explained. This independent verification adds credibility to their findings, dispelling doubts about the accuracy of their data.

While researchers believe these newly discovered planets are likely small, rocky worlds, determining their exact compositions is challenging due to their orbital alignment. The planets do not transit in front of Barnard’s Star from our viewpoint, meaning traditional methods for characterizing their atmospheres are unavailable. However, their close proximity to the star suggests that conditions may be too extreme for life as we know it.

Jacob Bean, a professor at the University of Chicago, expressed his excitement about the discovery, stating, “We just couldn’t wait to get this secret out.” The thrill of uncovering new knowledge about the universe propelled the research team throughout the project.

The four planets orbiting Barnard’s Star represent some of the smallest bodies confirmed using radial velocity techniques. So far, many rocky exoplanets discovered tend to be larger than Earth, and researchers are keen to examine whether these smaller worlds exhibit diverse compositions that could shed light on their formation processes. M dwarfs, like Barnard’s Star, are prevalent in the universe and are known for their intense magnetic activity, which could significantly influence planetary development.

Understanding these processes is essential for identifying which stars are most likely to support stable planetary surfaces. Although the newly discovered planets lie in inhospitable regions, researchers hope that insights gained from Barnard’s Star will inform future searches for extraterrestrial life. As technology continues to advance, astronomers are optimistic about refining their techniques to find planets in more temperate zones, increasing the likelihood of discovering habitable worlds.

The full study detailing these exciting findings is available in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. As we continue to explore the cosmos, each advancement in telescope technology brings us closer to uncovering the mysteries of the universe.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates. Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.