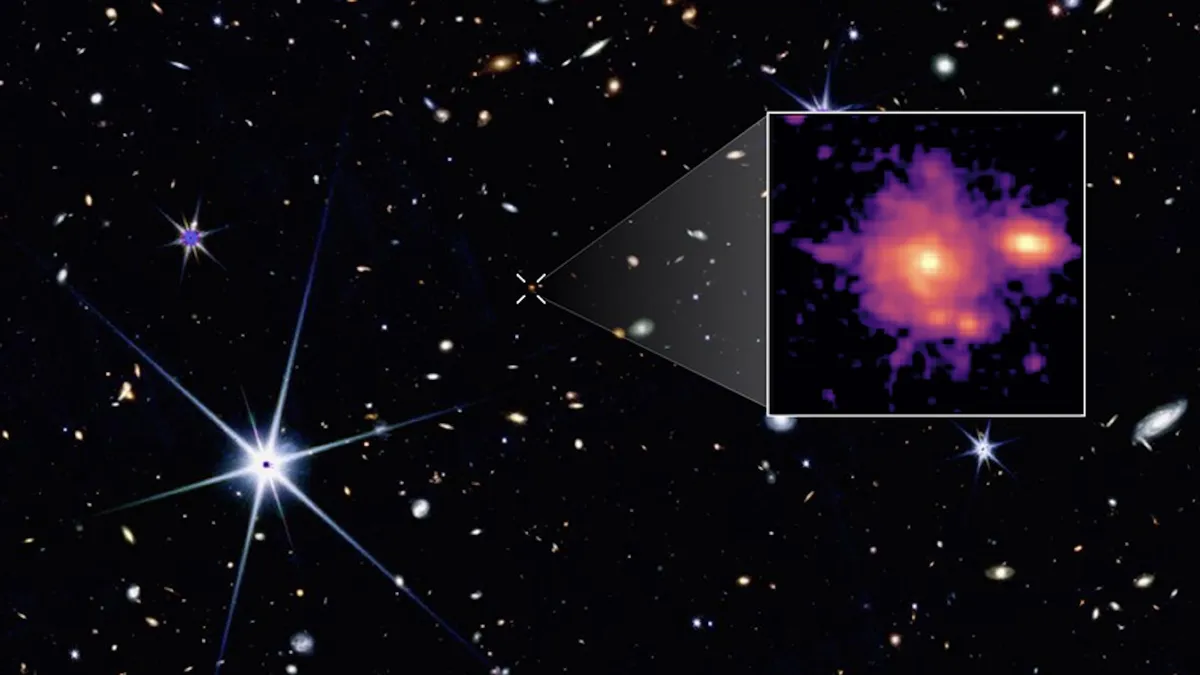

In a remarkable breakthrough, astronomers utilizing the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have made a serendipitous discovery that sheds new light on the early universe. They have identified a galaxy that strikingly resembles our own Milky Way, affectionately dubbed Zhúlóng. This ancient galaxy is waving its spiral arms back at us from a time when the universe was merely one billion years old, or about one-fourteenth of its current age.

The images captured by JWST reveal a galaxy that appears fully formed, complete with a central bulge of aged stars and a vibrant disk teeming with stellar newborns. Zhúlóng showcases two distinct spiral arms that echo the recognizable features of the Milky Way. Researchers have proclaimed Zhúlóng to be the most distant twin of the Milky Way ever observed, challenging our understanding of galaxy formation in the early cosmos.

The detection of a fully formed spiral galaxy like Zhúlóng at such an early stage in cosmic history raises significant questions. Current cosmological theories suggest that large galaxies typically require billions of years to form through a series of smaller galaxy mergers. However, the existence of Zhúlóng contradicts this notion, as it appears to have developed its impressive structure much quicker than anticipated. The full description of Zhúlóng was published on April 16 in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

What makes Zhúlóng particularly noteworthy is its resemblance to the Milky Way in terms of shape, size, and stellar mass. According to Mengyuan Xiao, the first study author and postdoctoral researcher at the University of Geneva, Zhúlóng's star-forming disk spans approximately 60,000 light-years across. In contrast, our Milky Way measures about 100,000 light-years in breadth and contains roughly 1.5 trillion solar masses compared to Zhúlóng's 100 billion. Despite its smaller size, Zhúlóng is still the largest Milky Way look-alike found at such an early point in the universe's history.

The discovery of Zhúlóng was entirely serendipitous, arising from the PANORAMIC survey, which is a wide-field survey aimed at mapping billions of distant objects. Conducted in JWST's innovative pure parallel mode, this technique allows the telescope to utilize two of its infrared instruments simultaneously, observing two separate regions of space at once. This capability is vital for identifying massive galaxies, which are exceedingly rare, according to Christina Williams, an assistant astronomer at the National Science Foundation's NOIRLab and principal investigator of the PANORAMIC survey.

The discovery of Zhúlóng adds to the growing body of evidence that demonstrates how JWST is reshaping our comprehension of the early universe. The telescope has consistently revealed that objects in this primordial time, including gargantuan galaxies and supermassive black holes, appear to have evolved too rapidly for existing theories to adequately explain. While the Milky Way took billions of years to form, Zhúlóng seems to have achieved a comparable structure in under a billion years, leaving researchers pondering how this is possible.

As the implications of this discovery unfold, the research team is proposing additional follow-up observations using both JWST and the ground-based Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in the Chilean desert. These observations aim to deepen our understanding of Zhúlóng and explore the characteristics of our galaxy's long-lost twin.

The revelation of Zhúlóng is not just about discovering another galaxy; it represents a profound shift in our understanding of the universe's formative years. With each new finding from the James Webb Space Telescope, we are drawn closer to uncovering the mysteries of our cosmic origins.