A recent study reveals that the melting Antarctic ice is significantly slowing down the Earth's strongest ocean current, known as the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. Published on March 3 in the journal Environmental Research Letters, researchers have projected that the influx of cold meltwater could lead to a slowdown of up to 20% by the year 2050. This reduction in current strength could have profound implications for ocean temperatures, sea level rise, and the delicate Antarctic ecosystem.

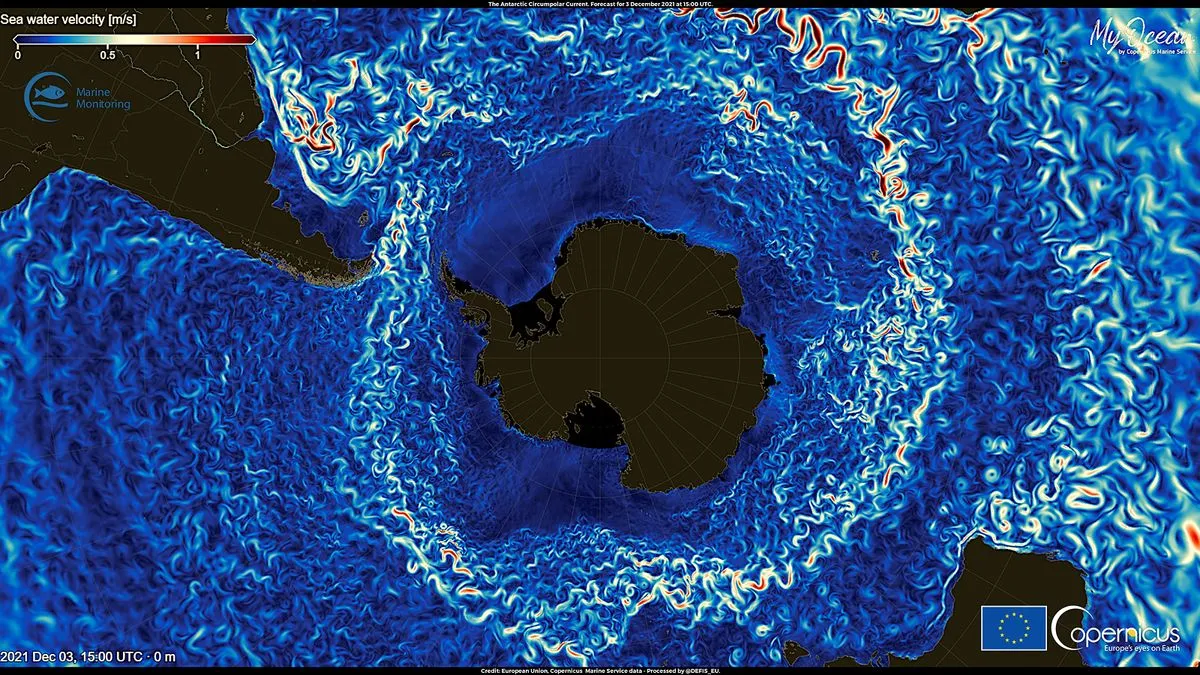

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current is a powerful ocean current that swirls clockwise around Antarctica, transporting an astonishing volume of approximately one billion liters (264 million gallons) of water every second. This current plays a crucial role in maintaining the climate by keeping warmer waters away from the Antarctic Ice Sheet and connecting the Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, and Southern Oceans. It serves as a vital pathway for heat exchange between these major bodies of water.

In recent years, climate change has accelerated the melting of Antarctic ice, resulting in a significant influx of fresh, cold water into the Southern Ocean. To analyze the impact of this phenomenon on the Antarctic Circumpolar Current's strength and circulation, researchers, including fluid mechanist Bishakhdatta Gayen from the University of Melbourne, utilized Australia’s fastest supercomputer along with a sophisticated climate simulator. Their findings indicate that the introduction of cold meltwater likely weakens the current by diluting the surrounding seawater, which in turn slows down the convection processes between the surface and deeper waters near the ice sheet.

As the Antarctic Circumpolar Current continues to weaken, the deep Southern Ocean is expected to warm over time due to decreased convection that brings colder surface water down. Additionally, meltwater will travel further north before sinking, altering the density profile of the world’s oceans and contributing to the current's slowdown. This change could allow warmer waters to reach the Antarctic Ice Sheet, exacerbating the already significant melting and further contributing to sea level rise.

Beyond its implications for climate, the Antarctic Circumpolar Current also serves as a critical barrier against invasive species. By directing non-native plants and animals away from the continent, the current helps maintain the biodiversity of the Antarctic ecosystem. A slowdown in this current could diminish its effectiveness as a barrier, allowing invasive species to migrate more easily to the Antarctic coastline. Gayen likens the current to a merry-go-round, explaining that if it slows down, the migration of species could occur much more rapidly.

Due to the remote location of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, it has not been monitored for a long time, making it challenging to differentiate between warming-induced changes and baseline conditions. Gayen emphasizes the necessity for a long-term monitoring record to better understand the current's dynamics and the changes it faces. The effects of this slowdown will not only be felt in the Southern Ocean but are likely to have ripple effects throughout all oceanic circulations, underscoring the interconnected nature of our planet's climate systems.

The findings of this study highlight the urgent need for proactive measures to address climate change and its impacts on ocean currents. As the Antarctic Circumpolar Current slows due to melting ice, the consequences will extend far beyond Antarctica, affecting global ocean circulation patterns and ecosystems. It is imperative that we continue to monitor these changes to better understand and respond to the challenges posed by a warming world.