Deep beneath the Earth’s surface, an extraordinary discovery has been made: living microbes sealed within a fracture of 2-billion-year-old rock. This remarkable finding expands our understanding of life's resilience and longevity. Lead researcher Yohey Suzuki, an associate professor from the Graduate School of Science at the University of Tokyo, expressed his excitement about the implications of this research. “We didn’t know if 2-billion-year-old rocks were habitable,” Suzuki noted. “Until now, the oldest geological layer in which living microorganisms had been found was a 100-million-year-old deposit beneath the ocean floor, making this discovery particularly thrilling.”

The rock sample that houses these ancient microbes was excavated from the Bushveld Igneous Complex (BIC) in northeastern South Africa. Spanning an area roughly the size of Ireland, the BIC is renowned for its rich ore deposits, including around 70% of the world’s mined platinum. Formed from slowly cooled magma, the BIC has undergone minimal changes over the millennia, providing a stable environment for microbial life to thrive.

The research team from the University of Tokyo, with support from the International Continental Scientific Drilling Program (ICDP)—a nonprofit organization that funds geological exploration—obtained a 30-centimeter-long core sample from approximately 50 feet below the surface. This rock varies in thickness up to 5.5 miles and has remained relatively undisturbed, making it an ideal habitat for organisms to persist over geological timescales.

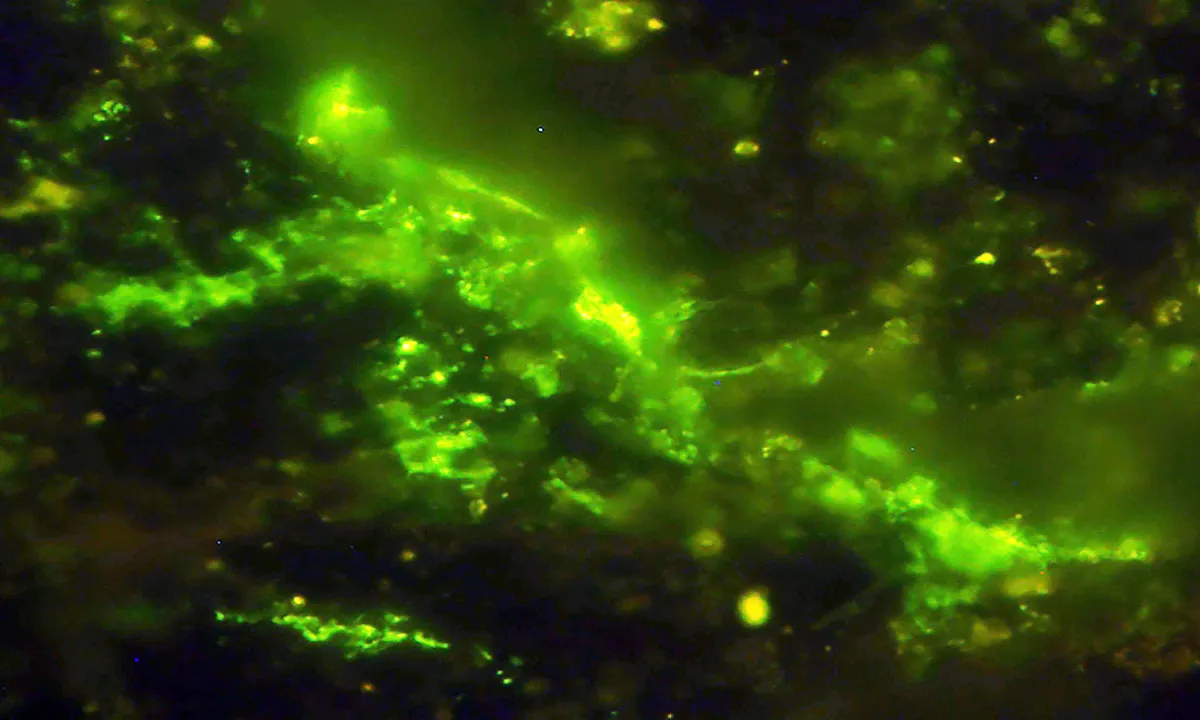

Upon analyzing thin slices of the rock, the research team discovered microbial cells densely packed into tiny cracks. These fractures were sealed off by clay, creating a closed system where the microbes could survive without outside interference. The cellular life appeared to exist in a state of slow motion, evolving scarcely over millions of years.

To confirm that the microbes were indigenous to the rock and not contaminants, the researchers employed a refined technique incorporating three types of imaging: infrared spectroscopy, electron microscopy, and fluorescent microscopy. By staining the DNA of the cells and examining the proteins and surrounding clay, they verified that the organisms were alive and native to the ancient sample.

One intriguing aspect of this discovery is the role of clay in preserving these ancient microbes. The clay acted as a natural barrier, sealing off the cracks and preventing anything from entering or leaving. This created a stable microenvironment where the organisms could survive for unimaginable lengths of time. Such natural encapsulation raises fascinating possibilities—could similar mechanisms exist elsewhere, perhaps even on Mars? If so, our chances of finding preserved life forms on other planets might be more promising than previously thought.

This groundbreaking discovery opens new avenues for studying the early evolution of life on Earth. The presence of organisms that have persisted in such ancient rocks allows scientists to peer back in time and understand how life may have adapted to extreme environments. “I am very interested in the existence of subsurface microbes not only on Earth but also the potential to find them on other planets,” Suzuki remarked. With NASA’s Mars Perseverance rover set to bring back rocks of a similar age as those studied, the excitement surrounding the potential for discovering ancient life is palpable.

The techniques developed in this study could be invaluable for examining rock samples from other planets. If microbes can survive sealed in rocks for billions of years on Earth, could similar life forms exist elsewhere in our solar system? This tantalizing question prompts scientists to consider the implications of their findings. The methods used to detect and confirm these ancient microbes could help identify signs of life in Martian rocks, especially with missions like Perseverance bringing back samples from Mars.

The notion that life can endure in isolation for such immense periods challenges our perceptions of survival and adaptation. These ancient microbes serve as living time capsules, offering a glimpse into life from eons ago. By studying these organisms, scientists hope to uncover clues about the conditions on early Earth and how life managed to take root. This finding also compels us to reassess the limits of life on our planet; if microbes can survive in extreme and isolated conditions, what does that reveal about life’s adaptability?

In summary, this discovery not only pushes the boundaries of geology and biology but also opens a new frontier in microbiology. The intersection of deep Earth studies and microbiology could lead to significant breakthroughs in understanding life’s resilience. Researchers will continue to explore these ancient habitats, utilizing perfected techniques to avoid contamination and ensure authenticity. As we look to the future, the implications of this research are vast. Could studying these ancient microbes help us prepare for discovering life beyond Earth? The answers may lie in continued exploration and cross-disciplinary collaboration. One thing is certain: the Earth’s deep places still have many stories to tell.

The full study was published in the journal Microbial Ecology.

—– Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates. Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com. —–