The Voting Rights Act, enacted during the U.S. civil rights era, stands as a pivotal law in the fight against discrimination in voting. Initially championed by Nobel Peace Prize laureate Martin Luther King Jr., this landmark legislation was passed by Congress and signed into law by Democratic President Lyndon Johnson in 1965. Over six decades later, the Act faces unprecedented challenges, particularly with the current composition of the U.S. Supreme Court, which holds a 6-3 conservative majority.

The Supreme Court is poised to make a significant ruling in the coming months regarding a case that centers on the congressional district map of Louisiana. This case, argued recently, raises concerns about potential changes to Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which is designed to prevent voting maps that dilute the voting power of minority groups. The conservative justices appear inclined to weaken this section, which could lead to systematic silencing of Black, Latino, Native, and Asian American voters, according to Sarah Brannon, deputy director of the American Civil Liberties Union's Voting Rights Project.

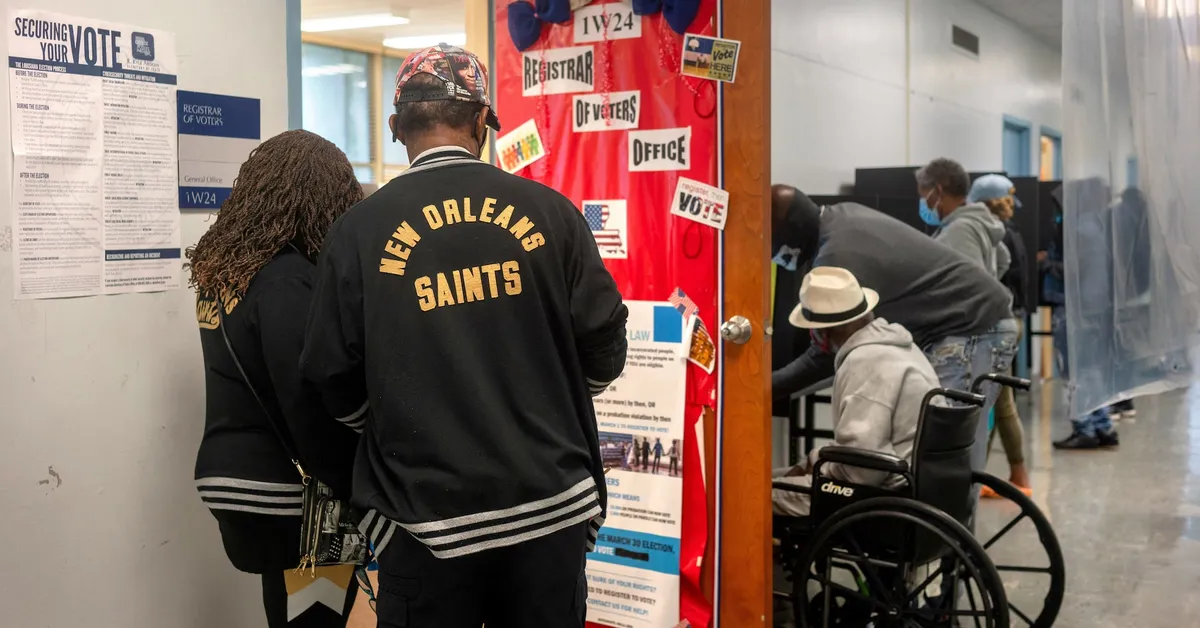

In Louisiana, Black individuals represent approximately one-third of the population, while white individuals make up the majority. The state has six congressional districts. Following a judicial ruling that deemed a previous map with only one Black-majority district as discriminatory, Louisiana's Republican-led legislature created a second Black-majority district. However, this decision was met with legal pushback from a group of white voters who claimed the map was overly influenced by race, violating constitutional protections that ensure equal voting rights.

The Trump administration backed the white voters' lawsuit but did not call for the complete invalidation of Section 2. Instead, it proposed a new framework that would impose stricter standards on cases involving Section 2, thereby limiting the role of race in redistricting. Justice Department lawyer Hashim Mooppan argued that the Constitution does not prohibit the consideration of race in districting but emphasizes that race should not override traditional, neutral principles.

This proposed framework aims to replace the standards established by the Supreme Court in the 1986 case, Thornburg v. Gingles, which had defined when an electoral map could be deemed unlawful due to its adverse effects on minority voting power. Critics, including law professor Spencer Overton from George Washington University, argue that this approach would effectively gut Section 2, making it nearly impossible for plaintiffs to succeed in legal challenges against discriminatory maps.

The process of redistricting, which occurs every decade following the national census, involves reconfiguring legislative district boundaries to reflect population changes. This process is typically controlled by state legislatures. The Trump administration's framework would impose new evidentiary burdens on Black voters challenging electoral maps, requiring them to provide statistics illustrating racial discrimination rather than partisan bias. Given that over 80% of Black voters tend to support Democratic candidates, separating race from party affiliation complicates these cases significantly.

The Voting Rights Act was designed to eliminate discriminatory voting practices prevalent in many Southern states, such as literacy tests. It was enacted shortly after the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited discrimination based on race in public accommodations, education, and employment. In 1982, Congress amended Section 2 to include a "results test," making it illegal to implement election practices that yield discriminatory effects, regardless of intent.

However, the Supreme Court has increasingly expressed constitutional concerns regarding the application of the Voting Rights Act. In a 2013 ruling involving Alabama's Shelby County, the Court removed the requirement for states with histories of racial discrimination to obtain federal approval before changing voting laws, further weakening the protections offered by the Act.

The most far-reaching outcome of the Supreme Court's impending decision could be the outright invalidation of Section 2. Benjamin Aguinaga, Louisiana's Republican solicitor general, has argued that Section 2's race-based redistricting requirements are unconstitutional. Justice Brett Kavanaugh, a Trump appointee and potentially pivotal vote, indicated support for the administration's approach, suggesting it might resolve many concerns regarding racial considerations in mapping.

If the Court decides to limit Section 2 litigation, it could significantly reduce the number of legal challenges to electoral maps based on racial grounds, benefiting the Republican Party, which holds a narrow majority in the House of Representatives. Groups such as Fair Fight Action and the Black Voters Matter Fund estimate that eliminating Section 2 could allow Republicans to redraw as many as 19 districts nationwide to their advantage.

As the Supreme Court deliberates on this critical issue, the future of the Voting Rights Act remains uncertain. While the ACLU's Sarah Brannon acknowledges the difficulty in predicting the Court's ruling, she affirms a commitment to continue advocating for fair electoral maps using every available tool. The stakes are high, as the integrity of the voting process and the representation of marginalized communities hang in the balance.