For a child who is not vaccinated against measles—one of the world’s most infectious viruses—no environment is entirely safe. Whether in a classroom, on a school bus, or in a grocery store, the risk of infection looms large. Research indicates that nine out of ten unvaccinated individuals exposed to an infected person will contract the virus. Once measles establishes itself in the body, it can lead to serious complications, damaging vital organs such as the lungs, kidneys, and brain. With vaccination rates in the U.S. declining, health experts warn that hundreds or even thousands more cases could arise, following recent outbreaks that have resulted in over 580 cases and at least one death.

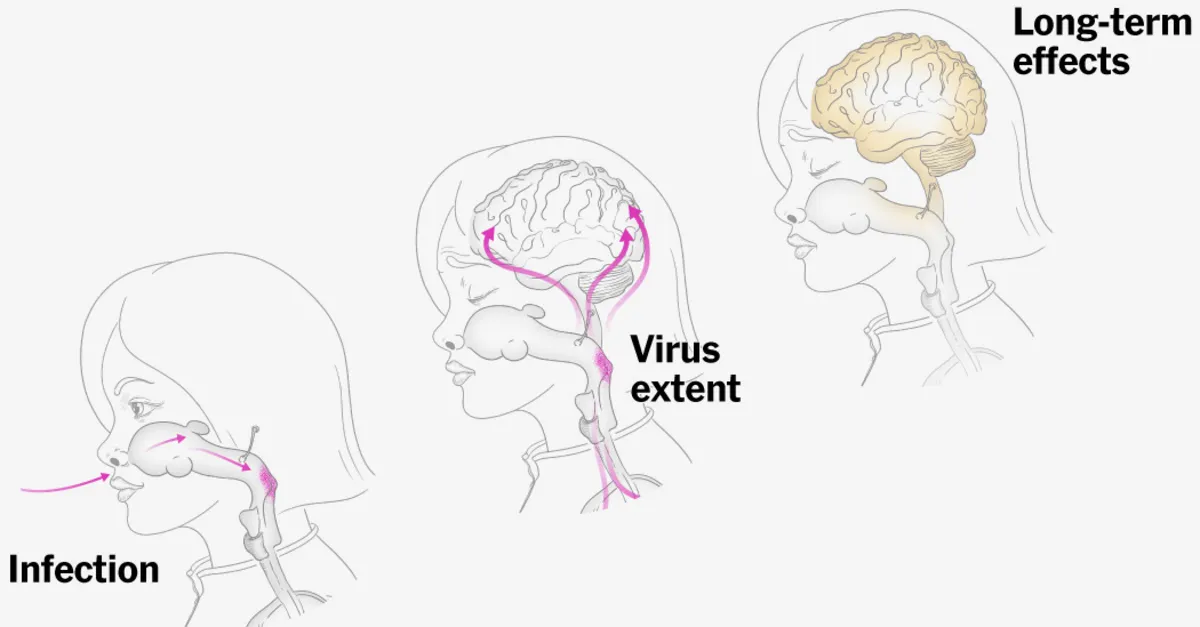

Measles is particularly insidious because it can linger in the air for up to two hours after an infected person has left a space. A child can unknowingly inhale droplets containing the virus in a room where another child had been playing or studying just an hour earlier. The virus can enter the body through the lining of the nose or mouth, or even through contact with the eyes. Within 24 hours, the virus takes hold by invading the nasopharynx cells located in the upper throat and subsequently spreads to the lungs, multiplying rapidly within the cells to build an army for an attack.

About a week following initial exposure, infected cells start traveling to various organs throughout the body. During this time, an immune response would typically occur in a vaccinated child, allowing their body to fight off the virus. However, unvaccinated children often do not exhibit symptoms during the early stages of infection. The average incubation period for measles is approximately two weeks, though it can vary between one to three weeks.

As the viral load increases, the virus spreads to infect cells in the lungs and eyes, leading to illness. A couple of weeks after inhaling the infectious droplets, children may start to feel unwell. Symptoms typically begin with general malaise and fever, followed by redness and irritation in the eyes, a cough, and a stuffy nose as the mucus membranes and nasal passages become inflamed. Some children may develop small, whitish-gray bumps on the inner lining of their cheeks, though these can go unnoticed or may not appear at all.

The hallmark of measles is the eruption of a distinctive red rash, which typically starts on the face and spreads down the neck, trunk, and limbs. Many of these initial symptoms tend to resolve on their own; however, the rash can persist for up to a week, gradually fading in the same order it appeared. Notably, a cough may linger for two weeks even after other symptoms have subsided. If a fever continues beyond the third or fourth day of the rash, complications may be developing, indicating a more severe case of the illness.

Even as the rash begins to fade, the infection can spread to the lungs and other organs, leading to severe complications. Children are often taken to the hospital after having the rash for several days, with many presenting low oxygen levels and difficulty breathing. Dr. Summer Davies, a pediatrician at Covenant Children’s Hospital in Lubbock, Texas, has treated numerous measles cases since an outbreak began in late January. She notes that many families are surprised when their seemingly healthy children rapidly decline in health.

The mild symptoms can escalate to a high fever reaching 104 or 105 degrees for several days. Poor fluid intake, sore throat, and diarrhea can contribute to dehydration, which poses additional risks, particularly for younger children whose smaller anatomy makes them more vulnerable. Approximately one in 20 children with measles may develop pneumonia, which can be fatal. Dr. Davies reports that many children admitted to her hospital recently had pneumonia caused by either the measles virus or a secondary pathogen that took advantage of their weakened immune systems.

One significant consequence of measles is what researchers term “immune amnesia,” a condition where the virus temporarily weakens the immune system. This results in children losing the protection they have built up against other infections, leaving them vulnerable for months or even years. About one in 1,000 children who contract measles will develop encephalitis, leading to potential permanent damage. For immunocompromised infants or children, a condition known as measles inclusion body encephalitis (MIBE) can occur, resulting in mental changes and seizures that often culminate in coma and death.

Additionally, another degenerative condition called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) can manifest up to a decade after a measles infection. Symptoms typically begin with behavioral changes and academic decline, progressing to seizures and coordination issues, ultimately leading to death, with a mortality rate approaching 95 percent. Erica Finkelstein-Parker, a mother from Pennsylvania, tragically lost her 8-year-old daughter, Emmalee, to SSPE. Unbeknownst to her, Emmalee had contracted measles before her adoption. Over time, Emmalee exhibited troubling symptoms, and doctors ultimately informed her family that there was no cure.