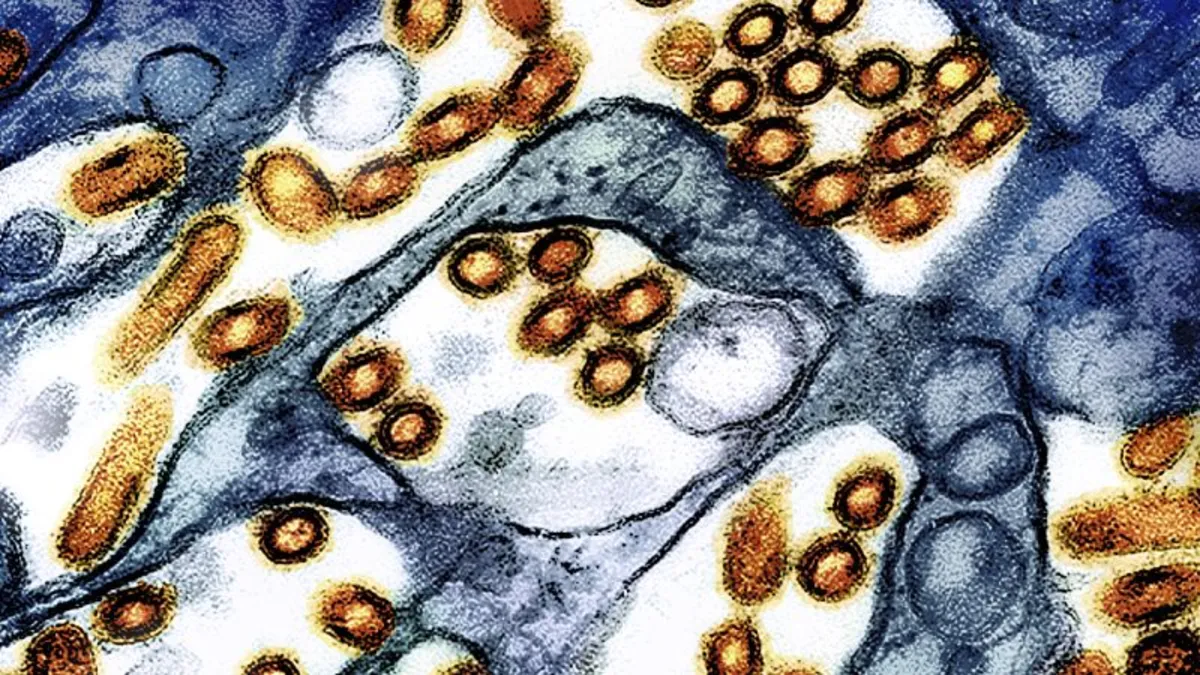

A recent study conducted by researchers at Cornell University and funded by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reveals alarming findings regarding raw cheese made from milk sourced from dairy cattle infected with bird flu. The study indicates that this type of cheese can harbor the infectious H5N1 virus for months, posing potential risks to public health.

Raw milk cheeses are products made with milk that has not undergone heat treatment or pasteurization, a process typically employed to eliminate harmful germs. While federal regulations prohibit the interstate sale of raw milk, the sale of raw milk cheese is legal nationwide, provided it is aged for at least 60 days before reaching consumers. This aging requirement, established in 1949, was intended to minimize contamination risks by allowing the development of natural acids and enzymes believed to kill pathogens.

However, the recent findings challenge the efficacy of this aging process. The study reveals that the aging of cheese may not effectively inactivate the H5N1 virus, raising concerns about the consumption of raw or undercooked foods, especially amidst ongoing outbreaks affecting dairy cattle, poultry, and various animal species. Previous research by the same team highlighted that the H5N1 virus can remain infectious in refrigerated raw milk for up to eight weeks.

Dr. Diego Diel, the lead researcher and an associate professor of virology at Cornell, explains that the virus's stability in milk and cheese may be due to the protective molecular matrix surrounding it. “The protein and fat content in cheese and milk create a favorable environment for the virus to survive at refrigeration temperatures,” he stated.

In light of these findings, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the secretary of the US Department of Health and Human Services, has asserted that food does not pose a risk for bird flu transmission. He claims, “The disease is not passed through food, so you cannot get it from an egg or milk or meat from an infected animal.” However, this statement is only partially accurate. There have been instances where cats and other animals contracted the virus from raw cow’s milk and raw pet food. Moreover, three confirmed human infections have occurred without a clear source of exposure to the H5N1 virus.

While there have been no verified cases of illness linked to the consumption of bird flu-contaminated foods, dairy workers have faced infections from splashes of raw milk. Dr. Diel emphasizes that it remains uncertain whether human infection can occur through the ingestion of contaminated food, adding, “I do think it is possible. There is a risk of infection,” contingent on the quantity consumed and the specific strain of the virus present.

The study involved creating mini cheeses using milk spiked with the H5N1 virus, testing them at three different pH levels: 6.6, 5.8, and 5.0. The team monitored the cheeses over time to assess the infectivity of the virus. Initial results showed high levels of the virus remained for the first seven days post-production, with a slight drop in the less acidic cheeses. Notably, the virus retained its infectious capacity throughout the entire two-month aging period, demonstrating remarkable stability.

The researchers also examined samples of raw milk cheese produced from infected cows, confirming that infectious virus levels persisted throughout the aging process. Their findings suggest that increasing the acidity of raw milk cheese could potentially eliminate the virus. Notably, no live virus was detected in cheese made at the lowest pH level of 5.0.

Experts highlight that pasteurized products are significantly safer. Previous studies have consistently shown that common pasteurization methods effectively inactivate the H5N1 virus. Dr. Seema Lakdawala, an associate professor of microbiology at Emory University, noted that milk can alter the pH required to inactivate the virus, emphasizing the need for continued vigilance in monitoring food safety.

In response to the study's findings, the FDA has released preliminary results from its own sampling study of raw cheese, testing 110 samples across the country. So far, 96 samples have tested negative for the virus, indicating that they likely were not made from contaminated milk. The FDA has also confirmed that all tested pasteurized dairy products, including milk and ice cream, were negative for viable H5N1.

In conclusion, the findings from this study serve as a crucial reminder of the importance of food safety and the potential risks associated with consuming raw milk products. Experts advocate for increased surveillance and emphasize the necessity of consuming only pasteurized dairy products to mitigate the risks associated with bird flu.