In recent years, the importance of the measles vaccine has come into sharp focus, especially as reports indicate a resurgence of this highly contagious and potentially life-threatening respiratory virus in various parts of the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that as of March 7, 2023, there have been 222 confirmed cases of measles across 12 jurisdictions in the U.S., from New York City to Alaska. This number is alarming, as it nears the 285 cases recorded throughout the entire year of 2024. A tragic event in February highlighted the severity of the situation, as a child died from measles in West Texas, marking the first measles-related death in the U.S. since 2015.

The outbreak in Texas is one of three reported so far this year, with the child being school-aged and unvaccinated against measles. Despite the fact that measles was declared "eliminated" in the U.S. in 2000, sporadic infections have emerged over the years, primarily among individuals who traveled internationally. Notably, in 2024, the CDC documented 16 measles outbreaks in the U.S., accounting for a staggering 69% of all reported cases.

As the situation evolves, many adults are questioning whether they should receive a measles booster shot or their first vaccination. The decision depends on several factors, including personal health history and vaccination records. Dr. Scott Roberts, an infectious diseases specialist at Yale Medicine, advises that individuals living in areas without outbreaks may not need to worry immediately, but cautions that geographical risk can change rapidly. He emphasizes the extreme contagiousness of measles, which is one of the most infectious diseases known.

Measles typically begins with a cough, fever, runny nose, and watery eyes, symptoms that can appear 7 to 14 days post-infection. About three to five days after these initial symptoms, a distinctive red rash develops, starting on the face and then spreading down the body. Measles can lead to severe complications, including deafness, pneumonia, brain swelling, and even death. Vulnerable populations include children under 5, pregnant women, and individuals with weakened immune systems.

Dr. Roberts notes that measles can compromise the immune system, increasing the risk of infections from other viruses and bacteria. It can also lead to keratitis, which may result in blindness. Survivors of measles face a higher risk of developing sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), a degenerative brain disorder with severe symptoms.

Measles is notably more contagious than both the flu and COVID-19. The basic reproductive number (R0) for measles ranges from 12 to 18, meaning an infected person can spread the virus to 12 to 18 individuals who lack immunity. The virus can be transmitted four days before to four days after the appearance of the rash, surviving on surfaces or in the air for up to two hours. Outbreaks often occur when infected individuals travel to areas with low vaccination rates, making unvaccinated populations particularly vulnerable.

However, communities with high vaccination rates can achieve herd immunity, significantly reducing the likelihood of an outbreak. Dr. Roberts emphasizes that the measles vaccine represents a remarkable success story in public health, showcasing the effectiveness of vaccination in controlling such a contagious disease.

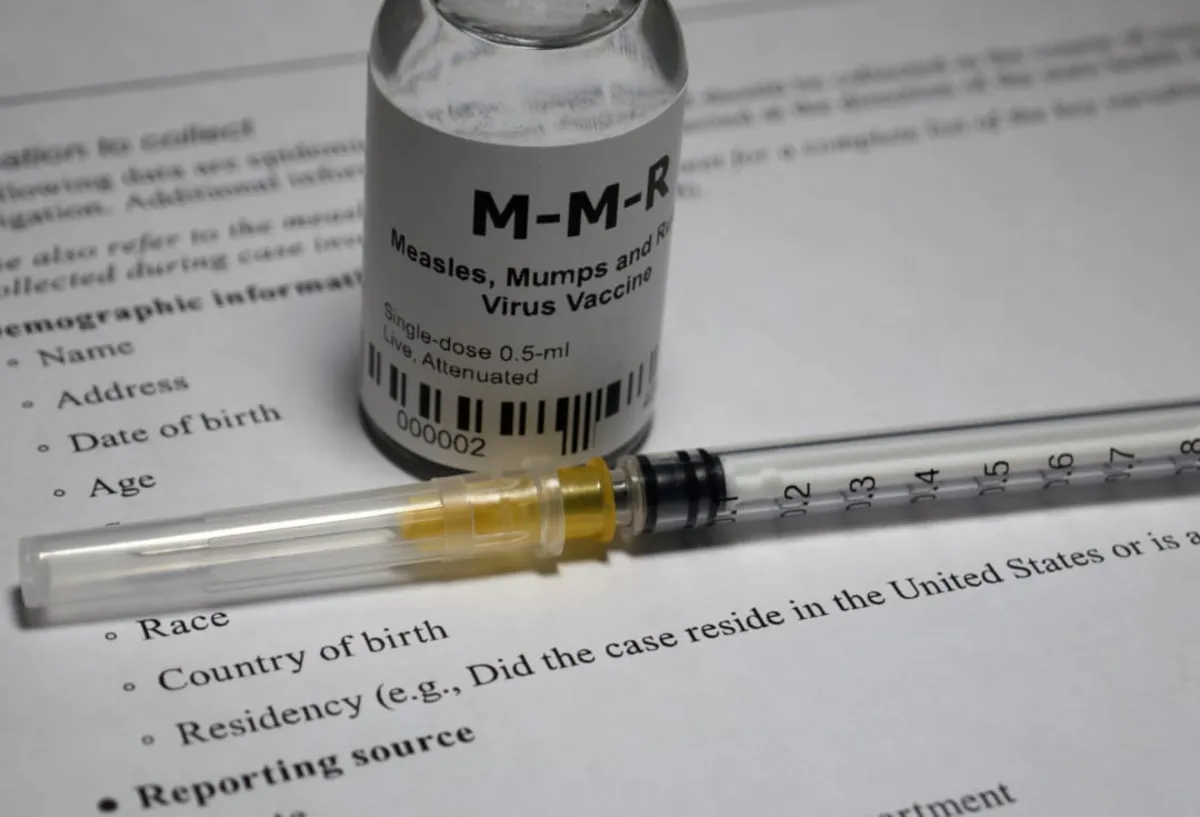

The MMR vaccine is administered in two doses, typically given to children at ages 12-15 months and again at 4-6 years. This live vaccine contains a weakened form of the virus, training the immune system to recognize and combat measles, mumps, and rubella. While no vaccine guarantees 100% effectiveness, two doses of the MMR vaccine are approximately 97% effective against measles.

Most vaccinated individuals will not contract measles; however, a small percentage may experience “breakthrough” cases with milder symptoms. The CDC finds the MMR vaccine to be safe, with most individuals experiencing no side effects. Common side effects, when they do occur, include soreness at the injection site, mild fever, rash, and joint pain.

Fortunately, most people have immunity to measles through vaccination or prior infection. The two doses of the MMR vaccine provide lifelong immunity, and individuals born before 1957 are generally considered immune due to widespread infection during childhood. However, healthcare workers born before this year without proof of immunity are encouraged to receive the vaccine.

Adults who have never been vaccinated or lack documentation of their vaccination status should receive at least one MMR dose. Certain groups, including college students, healthcare workers, and women of childbearing age, should receive two doses at least 28 days apart. Additionally, anyone over 6 months old planning to travel internationally should ensure they are fully vaccinated.

Adults who received the measles vaccine prior to 1968, which was less effective than the current formulation, should consider revaccination. For those unsure about their vaccination status, the CDC provides resources for obtaining vaccination records, including state Immunization Information Systems (IIS) and the option for antibody testing.

If you determine you need a measles vaccination, it is crucial to consult your healthcare provider to verify eligibility. Dr. Roberts warns that because the MMR vaccine is a live vaccine, it is not suitable for everyone, particularly individuals with weakened immune systems or those undergoing specific medical treatments. The vaccine is generally not administered to children under one year but may be given to infants as young as 6 months if they are traveling internationally or are in an outbreak area.

For a comprehensive list of contraindications and further details on the measles vaccine, the CDC website is an invaluable resource. As the situation continues to evolve, staying informed and proactive about measles vaccination can help protect not just individuals, but entire communities.