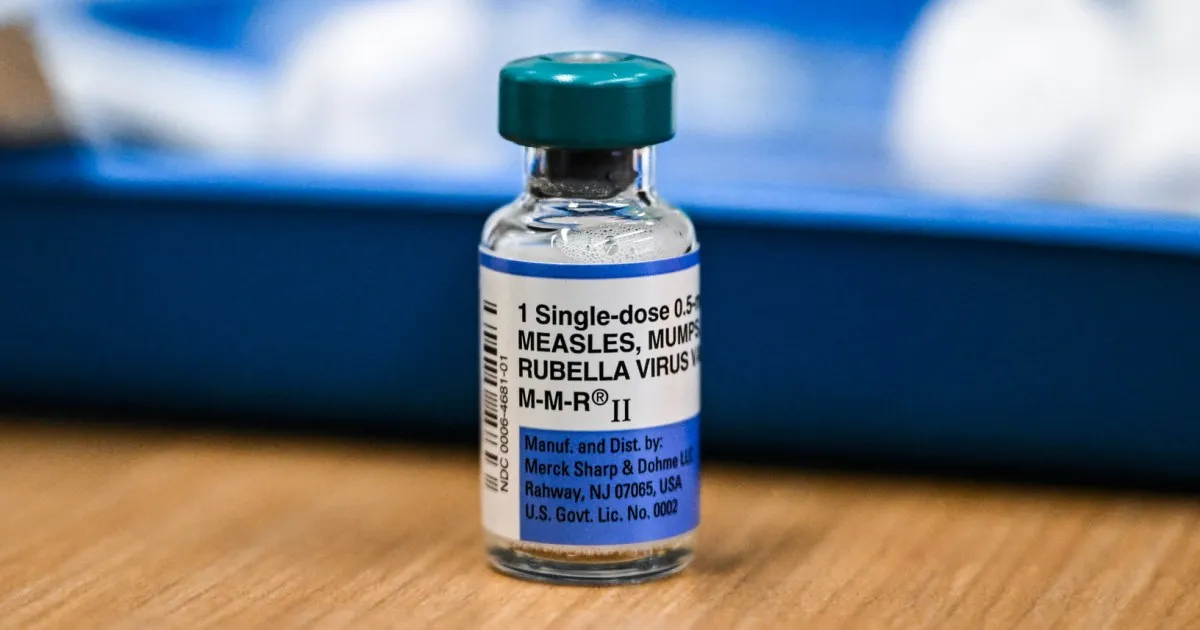

As of October 2023, more than 800 people in the U.S. have contracted measles, according to data from NBC News. The majority of these cases have been reported in West Texas, where an ongoing outbreak that began in January shows no signs of subsiding. Alarmingly, nearly all cases are among individuals who have not been vaccinated, although 3% of the identified cases are classified as breakthrough infections. These breakthrough cases occur when individuals fall ill despite being either partially or fully vaccinated with the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine.

Infectious diseases experts stress that the MMR vaccine is one of the most effective vaccines available. Rodney Rohde, a professor at Texas State University, explains that while the vaccine offers strong protection, a small percentage of vaccinated individuals may still contract measles during a large outbreak. Specifically, one dose of the MMR vaccine is 93% effective at preventing measles, while the second dose boosts that effectiveness to 97%.

“The vaccine is highly effective,” Rohde states. “However, it does mean that after two doses, while 97 out of 100 individuals will develop strong immunity to measles, the remaining three could still be vulnerable.” This has led to claims circulating on social media from vaccinated individuals who experienced breakthrough infections, resulting in serious illness. Rohde acknowledges that this scenario is “slightly possible,” suggesting that these individuals might belong to that small percentage who did not respond adequately to the vaccine.

Research indicates that even when breakthrough infections occur, the MMR vaccine usually provides some level of partial protection. “If someone vaccinated does contract measles, it’s often a milder version, sometimes referred to as modified measles,” Rohde explains. In such cases, the characteristic rash may be less widespread, fainter, or atypical, not following the classic pattern of starting at the hairline and spreading downward. Additionally, fever is generally milder or even absent.

Classic measles can result in fevers exceeding 104 degrees Fahrenheit, whereas modified cases usually present with lower-grade fevers. Other common measles symptoms, such as cough, runny nose, and conjunctivitis (red eyes), may still manifest but are often less intense in breakthrough cases. Rohde notes that Koplik spots, tiny white spots in the mouth, are less frequently observed in these scenarios. While breakthrough cases are generally less contagious, they still pose a risk for transmission, as individuals are contagious four days before and four days after the onset of the rash.

Timing can significantly impact the effectiveness of the MMR vaccine. A child who has recently received the vaccine may remain vulnerable for the first couple of weeks, especially during intense outbreaks. Rohde emphasizes that it typically takes the human immune system about two weeks to develop adequate protection against the measles virus. If exposed just before or after vaccination, the body may not be fully equipped to fend off the virus.

Some individuals, particularly those born with weakened immune systems or who develop conditions like autoimmune diseases or blood cancers, may not mount a robust immune response against measles, thereby increasing their risk of breakthrough infections. Weaver adds, “There are individuals with overall immune systems that are less effective against various infectious agents.”

The risk of developing a breakthrough measles infection may also depend on when an individual was born. Before the first measles vaccines were introduced in the 1960s, most people contracted the virus during childhood, providing lifelong immunity to those who survived. However, individuals born between 1957 and 1968 received a first-generation measles vaccine made with an inactivated virus, which was less effective. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that anyone born during this time frame should receive at least one dose of the MMR vaccine.

Moreover, people who received only a single MMR dose between 1968 and 1989 may have reduced protection compared to those who have received the standard two doses over the past several decades. Dr. William Schaffner, a professor of preventive medicine and infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University, suggests that those who had only a single dose and are near a current measles outbreak or traveling to areas where measles is endemic should consult with a healthcare provider about the possibility of receiving another dose.

As the U.S. grapples with the resurgence of measles, the importance of vaccination cannot be overstated. Understanding the nuances of breakthrough infections and the implications of vaccination timing is crucial in combating this highly infectious disease. With continued public health efforts and vaccination campaigns, the goal remains to eradicate measles and protect communities across the nation.