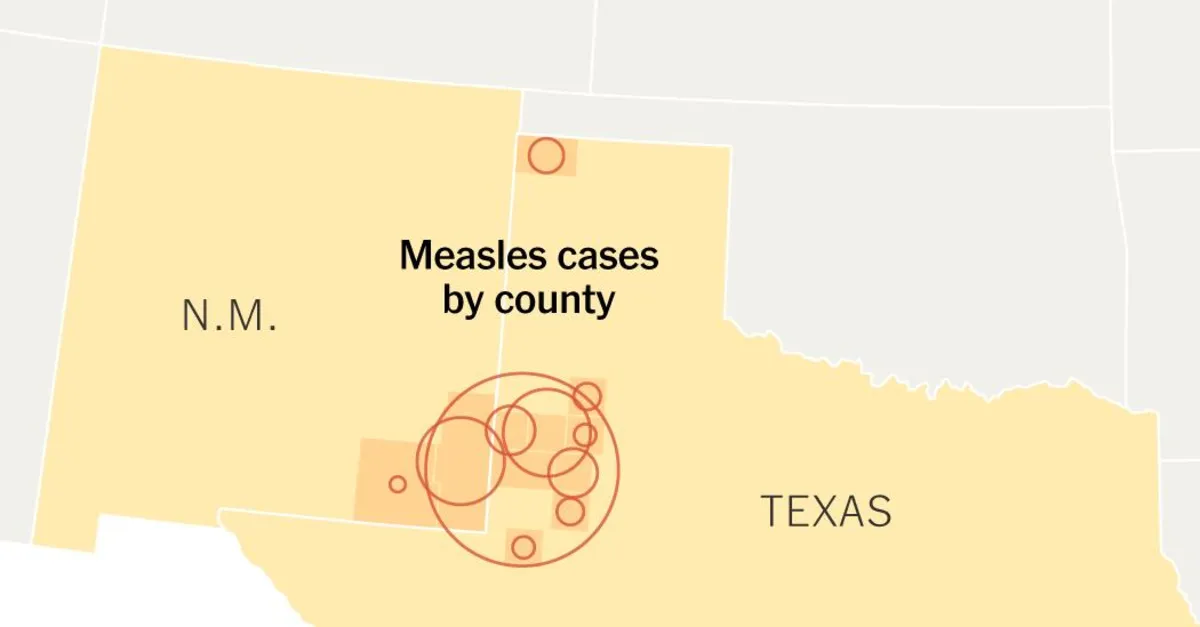

Measles continues to spread alarmingly in West Texas and New Mexico, with over 250 confirmed cases, primarily among unvaccinated school-age children. The situation has escalated, prompting state health officials to take action. Additionally, two cases in Oklahoma have been linked to these outbreaks, although specific locations for these cases have not yet been disclosed. Eleven other states have reported isolated cases of measles, mostly associated with international travel.

The outbreak in Texas began in late January, when health officials in Gaines County, a rural agricultural area on the western edge of the state, reported two initial cases. Since then, the situation has rapidly deteriorated, with measles spreading into neighboring counties and infecting at least 223 individuals by Tuesday. Among these cases, 29 people have been hospitalized, and tragically, an unvaccinated young child has died—the first measles-related death in the United States in a decade.

New Mexico has also declared an outbreak in Lea County, which borders Gaines County. While officials have not officially confirmed a direct connection between the New Mexico cases and the Texas outbreak, they have stated that the cases are “undoubtedly related.” Recently, an unvaccinated resident in Lea County tested positive for the virus and subsequently died, although the cause of death has not yet been confirmed as measles.

The majority of measles cases in both Texas and New Mexico are concentrated among individuals who are unvaccinated or whose vaccination status is unknown. Gaines County has historically low childhood vaccination rates, largely influenced by the area's sizable Mennonite community. Although there is no religious doctrine explicitly prohibiting vaccinations, this insular group tends to avoid interaction with the healthcare system and often relies on home remedies and supplements. As of last year, only 82 percent of kindergarten students in Gaines County received the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine (M.M.R.), well below the 95 percent coverage needed to effectively prevent outbreaks.

In Texas, public schools mandate certain vaccinations, including the M.M.R. shot; however, parents can apply for exemptions on “reasons of conscience,” including religious beliefs. Gaines County reported one of the highest exemption rates in the state last year. Vaccination rates can also significantly vary by school district. For instance, the Loop Independent School District in Gaines County, which consists of one school, had the lowest M.M.R. vaccination rate among affected counties, with only 46 percent of kindergarten students vaccinated in the 2023 school year, a drastic decline from 82 percent in 2019.

In contrast, Lea County, New Mexico, boasts a relatively high M.M.R. vaccination rate among children and teens, sitting at approximately 94 percent. However, the vaccination rate among adults is concerning, with only 63 percent having received one shot of the M.M.R. vaccine and just 55 percent fully vaccinated with both doses, according to local health officials. They also noted that some vaccinated adults might not have their records updated in the system, complicating the true vaccination landscape. Adults account for over half of the reported measles cases in New Mexico.

Measles is known to be one of the most contagious infections. In a theoretical community where no one is immune, each infected person could transmit the virus to 18 others, leading to an outbreak that spirals out of control. To effectively curb the spread, it is crucial that at least 94 percent of the community is vaccinated. While measles symptoms typically resolve within a few weeks, the virus can pose severe health risks, including pneumonia, which can hinder oxygen intake in children, and brain swelling, which can result in lasting damage.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), for every 1,000 children who contract measles, one or two will succumb to the illness. Furthermore, measles can induce “immune amnesia,” compromising the body’s ability to fight off previously encountered illnesses and increasing susceptibility to future infections. Unfortunately, once someone contracts measles, there is little that doctors can do to mitigate its severity, as there is no antiviral treatment available. This underscores the importance of receiving two doses of the M.M.R. vaccine, which are 97 percent effective at preventing infection.

As the measles outbreak continues to evolve, public health officials emphasize the critical need for vaccination to protect communities and prevent further outbreaks.