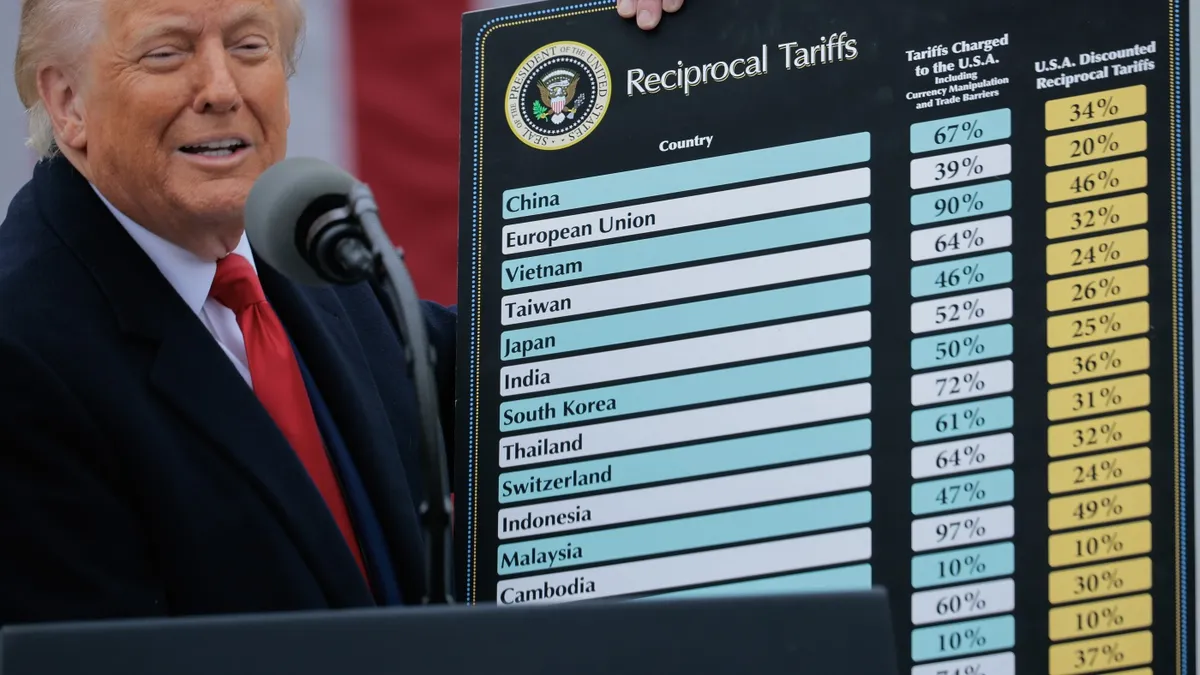

This week was initially set as the deadline for various countries to finalize trade deals with the U.S. or face potential tariffs of up to 49% on their goods sold in the United States. While President Trump continues to threaten high import taxes, he has now postponed the effective date to August 1, which has introduced further uncertainty into the trade landscape. In this article, we provide a comprehensive update on Trump's tariff policy, detailing the current tariffs in place and the countries affected.

Starting in April, President Trump implemented a minimum tariff of 10% on nearly all U.S. imports, with certain exceptions such as cellphones and computers. Notably, imports from China are subjected to a significantly higher tariff rate of 30%. This has resulted in the average tariff rate reaching its highest level since the 1930s. According to a daily tracker from the Bipartisan Policy Center, the U.S. government collected nearly $30 billion in tariff revenue during June, representing a threefold increase from March, prior to the announcement of worldwide tariffs. Although foreign companies may absorb some of these tariff costs, the majority of the burden falls on U.S. businesses and consumers.

Many countries initially faced higher tariffs, such as a 24% tax on goods from Japan and a staggering 49% on goods from Cambodia. This news triggered a sharp sell-off in the stock market, prompting Trump to announce a 90-day pause on those elevated tariffs to facilitate trade negotiations. As this 90-day period comes to a close this week, Trump has once again indicated his intention to impose significantly higher tariffs, often mirroring the rates introduced in April. For instance, on Tuesday, he announced a potential 25% tariff on goods from Japan and South Korea but has delayed the effective date until August 1. While this postponement may offer short-term relief to affected businesses and purchasing managers, it does little to alleviate the broader uncertainty that continues to weigh on the U.S. economy, particularly in the manufacturing sector.

Wells Fargo economists Shannon Grein and Tim Quinlan noted that the ongoing uncertainty surrounding trade policy has created significant challenges for the U.S. economy. A recent report by the Institute for Supply Management indicated that tariffs have negatively impacted factory orders. The inconsistent nature of the trade policy, characterized by fluctuating tariffs, has led to price uncertainty for consumers, causing many to delay large capital purchases until a more stable environment emerges.

Currently, goods imported from China are taxed at a rate of 30%, which is notably higher than the tariffs imposed on imports from other countries. This rate is relatively low compared to the temporary tariffs that reached as high as 145%. Trump's frustrations stem from the fact that China exports significantly more to the U.S. than it imports, leading to a trade imbalance. He has also criticized China for not taking adequate measures to combat the fentanyl trade.

In April, Trump announced a 20% tariff on goods imported from the European Union, later reducing this to 10%. Although a new tariff rate for European products has yet to be confirmed, Trump hinted that it could reach as high as 50%. To date, the EU has refrained from imposing retaliatory tariffs on U.S. exports, but this situation may change if tensions escalate further.

Mexico and Canada were among the first nations targeted by Trump's tariffs this year. Initially, goods from these countries faced a 25% tariff (or 10% for Canadian energy). However, Trump later exempted products covered under the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), a trade deal he signed during his first term. This exemption was likely influenced by Mexico and Canada's actions to curb illegal immigration and fentanyl trafficking, as well as the backlash from investors and business leaders concerning the tariffs. Mexican and Canadian imports not covered by the USMCA still face a 25% import tax.

The U.K. and Vietnam are the only two countries that have successfully negotiated trade deals with the Trump administration. These agreements allow for increased U.S. access to their markets in exchange for limited tariffs on exports to the United States. Trump has maintained a baseline tariff of 10% on imports from the U.K., while imports from Vietnam are taxed at 20%. In April, Trump threatened to impose tariffs as high as 46% on Vietnamese goods, prompting some exporters to shift operations from China to Vietnam to benefit from these lower tariff rates.

In an effort to protect certain U.S. industries, Trump has imposed additional tariffs on specific goods. Imported steel and aluminum are currently subjected to a 50% tariff (25% for imports from the U.K.), while cars and auto parts face a 25% tax, with exceptions for products covered under the USMCA agreement. This strategy aims to avoid a repeat of the challenges faced during Trump's first term, when U.S. metal manufacturers paid higher prices for raw materials yet struggled to compete with cheaper imported finished goods.

The administration is also considering additional tariffs on specific categories of imports, including copper, pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, and lumber. However, many of these tariffs are facing legal challenges. Trump has implemented most of the tariffs under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), a 1977 statute. Several states and businesses have contested these tariffs, arguing that the IEEPA does not grant the president the authority to impose sweeping import taxes in response to a persistent U.S. trade deficit. A federal trade court agreed in May, striking down some tariffs, but they have remained in effect as the administration pursues an appeal. If the courts ultimately rule against Trump's tariffs, he may still have the authority to impose tariffs on specific goods, such as steel and aluminum, under other statutory provisions.